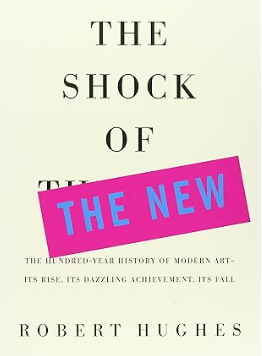

Back in the 1980s, I took a Humanities class during my freshman year of college. The professor was really good, and she supplemented her lectures by showing up a few episodes of Robert Hughes‘s BBC series Shock of the New, which covered the history of Modern Art as seen through Hughes’s own discerning, sardonic lens.

I remember being struck by how witty and intelligent Hughes seemed as he talked about numerous examples of iconic modern art and architecture. He did exactly what a good critic is supposed to do: open your eyes to meaning and resonance in art that you might have missed, and connections you never would have thought of.

I liked the series so much that I’ve watched it a couple of times since on YouTube, and I recently bought the book that Hughes wrote to accompany it. Hughes really was one the smartest and most interesting art critics of his generation, and he could really write. Take this passage, for instance, about Pablo Picasso’s most famous and disturbing work, Guernica,

Seen detached from its social context, if such a way of seeing were either possible or desirable (in Picasso’s view it would not have been, but there are still formalists who disagree), it is a general meditation on suffering, and its symbols are archaic, not historical: the gored and speared horse (the Spanish Republic), the bull (Franco) louring over the bereaved, shrieking woman, the paraphernalia of pre-modernist images like the broken sword, the surviving flower, and the dove. Apart from the late Cubist style, the only specifically modern elements in Guernica are the Mithraic eye of the electric light, and the suggestion that the horse’s body is made of parallel lines of newsprint, like the newspaper in Picasso’s collages a quarter-century earlier. [emphasis mine]

As I read this passage, I thought to myself: wow. Then I thought to myself: Mithraic? WTF is that? So, naturally, I googled it and discovered that Mithraism was a religious cult in 4th Century C.E. Rome that directly opposed Christianity and was popular with Roman soldiers. I don’t know exactly what sense Hughes was employing the word, but I think he was getting at the idolatrous aspect of Fascism—literally, an ideology opposed to Christ and Christian values—as manifested in the mid-Twentieth Century love of technology and machines. Reading Hughes’s moving and trenchant prose, I was reminded of how Picasso, eighty-seven years before Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer, Picasso painted the most powerful and grotesque indictment of war, and especially high-tech war, ever conceived. (Sadly, it is as relevant now as it was in 1937.)

If you have a chance, you should watch Shock of the New, or any of Hughes’s other series if you can find them. If nothing else, you’ll probably be smitten by his fascinating and highly idiosyncratic rhetorical style, with his strange (theoretically Australian) accent and tendency to punch words harder than Mike Tyson. My wife and I still joke lovingly about the way he pronounced various famous artists: i.e., Pehblo Pehkesso.

He was a treasure, and I miss him.