Of all the categories of genre fiction that I’ve consumed over my lifetime, fantasy has probably best the least represented. Sure, I love The Lord of the Rings, and The Narnia Chronicles, and the works of Ray Bradbury that I consider to be dark fantasy (see Something Wicked this Way Comes). But I don’t keep up with many modern fantasy writers nor read many contemporary fantasy novels.

So, you can imagine my surprise when I took a chance on Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi, a fantasy novel that made quite a splash when it came out in 2020, and I enjoyed the hell out of it. It’s a fascinating story of a man trapped in a labyrinth that he calls The House, and which is composed of endless Greco-Roman halls lined with innumerable statues and vestibules. There is a sky above and ocean tides below, which often flood the lower levels. The man is called Piranesi by the only other person (i.e., “the Other”) in The House, an older man who seems able to leave somehow, only to return with key supplies like vitamins and batteries, which he shares with Piranesi.

It’s a fascinating book, and unexpectedly suspenseful, too, especially when Piranesi begins having flashbacks of who he is and how he came to be in the House. This happens about the same time as the sudden appearance of mysterious, written messages that are scattered throughout the House. They seem to have been left by another, recent intruder (one who seems interested in helping Piranesi escape).

For me, at least half of the appeal of Piranesi lies in this whodunnit factor. Like the protagonist himself, I was caught up in the mystery of how he came to be there, who he is, and how he might get out. But the other half lay in the dizzying, intricate nature of the setting—the endless labyrinth that Piranesi inhabits. Such dreamlike settings are more common in literature than one might think, and their appeal is very much like that of a vivid, fabulously detailed diorama, of the sort that all children love to gaze into (and imagine themselves inside).

I don’t know what it is, exactly, about mazes, labyrinths, and castles that evokes the power of imagination, But I think it has to do with their endless novelty, the promise of infinite rooms and corridors that we, like children, would love to explore. More to the point, such structures also symbolize the power of imagination—especially the child-like imagination that each of us still harbors. That’s why there is such a grand tradition of castles and mazes in fantasy literature and mythology, from the Minotaur’s labyrinth to the vast, rambling ruins of the Gormenghast trilogy.

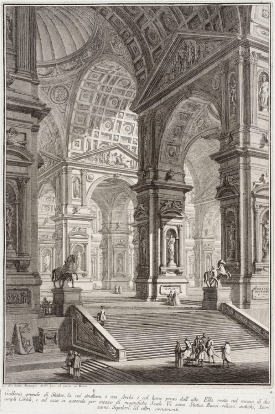

Clarke herself acknowledges this tradition in her main character, Piranesi, who is named after Giovanni Battista Piranesi, the 18th Century illustrator who was famous for his drawings of impossibly grand and complicated imaginary buildings. His most famous works are a series of etchings titled Carceri d’invenzione (Imaginary Prisons), and these are, themselves, part of a much older tradition of so-called capricci, drawings that depict architectural fantasy.

As I read Clarke’s novel, I was reminded of Steven Millhauser, whose postmodern short stories I read in graduate school. In particular, the story “The Barnum Museum” uses the same kind of capricci-style fantasy in its setting, that of the—fabulous, titular museum, placed in an unnamed city and an unspecified time. The story begins:

The Barnum Museum contains a bewildering and incalculable number of rooms, each with at least two and often twelve or even fourteen doorways. Through every doorway can be seen further rooms and doorways. The rooms are of all sizes, from the small chambers housing single exhibits to the immense halls rising to the height of five floors. The rooms are never simple, but contain alcoves, niches, roped-off divisions, and screened corners; many of the larger halls hold colorful tents and pavilions.

Some critics might point that Millhauser, who has won a Pulitzer Prize for his fiction, is a writer in the magical realism school of fiction, rather than fantasy per-se. Do such distinctions matter? Probably not. If pressed, I would say that Millhauser writes highly fantastic realism while Clarke writes highly realistic fantasy. But the technique, and the effect, is the same. Both works focus the reader on their own power of imagination, which the reader must contribute to the work to make it come alive.

Writers of fantasy (and science fiction, too) often become obsessed with world-building. There are countless essays and videos on the topic—how to create better and more compelling imaginary worlds. I haven’t read much on the topic, but I suspect that one mistake that novice writers often make is that they concentrate on building their world out, when they should focus on building it down. That is, they should be working on one or two key settings, digging down into them to find the magic of specificity.

Take this example from Ray Bradbury’s novel Something Wicked this Way Comes, which involves a sinister, supernatural carnival that appears in the fields overnight outside of town.

In the meadow, the tents, the carnival waited. Waited for someone, anyone to wade along the grassy surf. The great tents filled like bellows. They softly issued forth exhalations of air that smelled like ancient yellow beasts. But only the moon looked in at the hollow dark, the deep caverns. Outside, night beasts hung in midgallop on a carousel. Beyond lay fathoms of Mirror Maze which housed a multifold series of empty vanities one wave on another, still, serene, silvered with age, white with time. Any shadow, at the entrance, might stir reverberations the color of fright, unravel deep-buried moons. If a man stood here would he see himself unfolded away a billion times to eternity? Would a billion images look back, each face and the face after and the face after that old, older, oldest? Would he find himself lost in a fine dust away off deep down there, not fifty but sixty, not sixty but seventy, not seventy but eighty, ninety, ninety-nine years old? The maze did not ask. The maze did not tell. It simply stood and waited like a great arctic floe.

Once again, we have the labyrinth motif, this time in the form of the carnival’s mirror maze. What’s inside the mirror maze? The same thing that’s inside Piranesi’s endless House. Quite simply, it is…us. The Ego, with all its fears and desires. And imagination—our imagination—which, like Millhauser’s unfathomable museum, is bottomless.

It’s bottomless because the human imagination flows upward from the human subconscious—both the collective subconscious that Carl Jung spoke of, but also that of each person’s individual, unique subconscious. This leads us to another source of power in this subgenre—namely, the implicit threat of madness.

The playwright Jerome Lawrence wrote, “A neurotic is a man who builds a castle in the air. A psychotic is the man who lives in it.” We sense the truth of this when reading a work of Diaramic fiction, or viewing a work of Capriccio art. Somewhere in the endless labyrinth lies the death of the ego, the breakdown of the precious illusions that bind us to our daily reality.

It’s for this reason that I like to call this subgenre Vortex fiction—rather than Capriccio fiction or Caprice fiction or Dioramic fiction. The sense of a psychological vortex that is both enchanting and dangerous is the source of the work’s power. It’s what makes this kind of fiction so compelling, even mesmerizing.

No writer captured this threat of psychological implosion better than Juan Luis Borges, whose fiction was obsessed with mazes, labyrinths, infinity, and almost every other trope of this sub-genre. His most iconic short story is probably “The Library of Babel,” which describes an endless library. The story begins:

The universe (which others call the Library) is composed of an indefinite, perhaps an infinite, number of hexagonal galleries, with enormous ventilation shafts in the middle, encircled by very low railings. From any hexagon the upper or lower stories are visible, interminably. The distribution of the galleries is invariable. Twenty shelves—five long shelves per side—cover all sides except two; their height, which is that of each floor, scarcely exceeds that of an average librarian. One of the free sides gives upon a narrow entrance way, which leads to another gallery, identical to the first and to all the others.

The library contains every possible 410-page book based on a 25-letter alphabet, which means that, somewhere among its countless volumes, a near-infinity of literary masterpieces can be found. Unfortunately, these are, of course, outnumbered by a much, much, much larger number of books containing pure gibberish.

Trippy, huh? I am especially impressed that Borges wrote this story in 1941, long before terms like googol and permutation and information theory had entered into common parlance. Borges truly was the first modern writer to venture down the rabbit-hole of Vortex fiction.

If Vortex fiction really is a distinct sub-genre, then it has the peculiar distinction of being one that spans two parent genres: fantasy and magical realism. Dioramas, after all, must be realistically detailed in order to kindle our imaginations, but they are also, obviously, works of fantasy, miniature caprices designed to both mimic and transcend reality.

If you’re looking for a good introduction to Vortex fiction, you couldn’t do better than Clarke’s Piranesi. I encourage everyone to check it out. Or, heck, you can go up to Step Away magazine and check out this free short story, which is my own, personal attempt at Vortex fiction. (Yes, I’m closing this blog post with another shameless plug.) Enjoy!