In the summer of 1982, I was a very unhappy boy. Being a nerd in an upper-class high school full of preppies and jocks, I didn’t fit in very well. I hated most of my classes. I had a few good, close friends (including some jocks), but that was it. As one would expect, I spent a lot of time in my room reading sci-fi novels and typing short stories on the typewriter my mother had bought me.

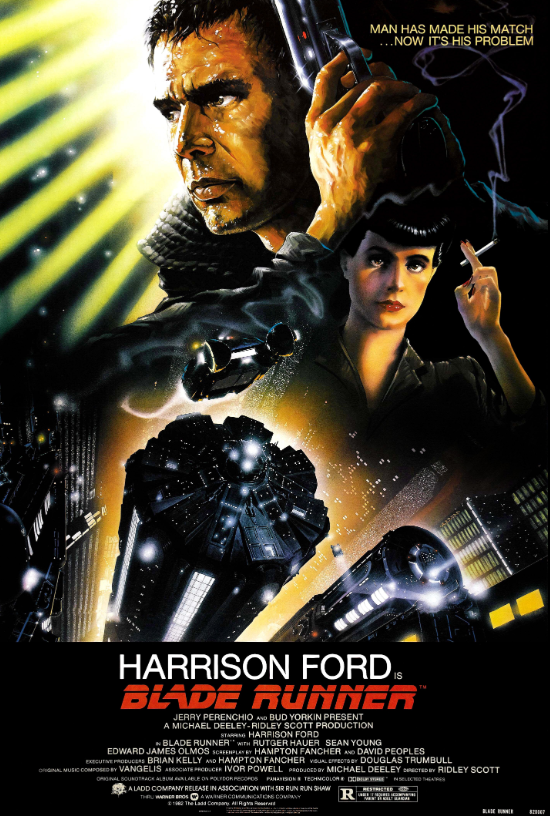

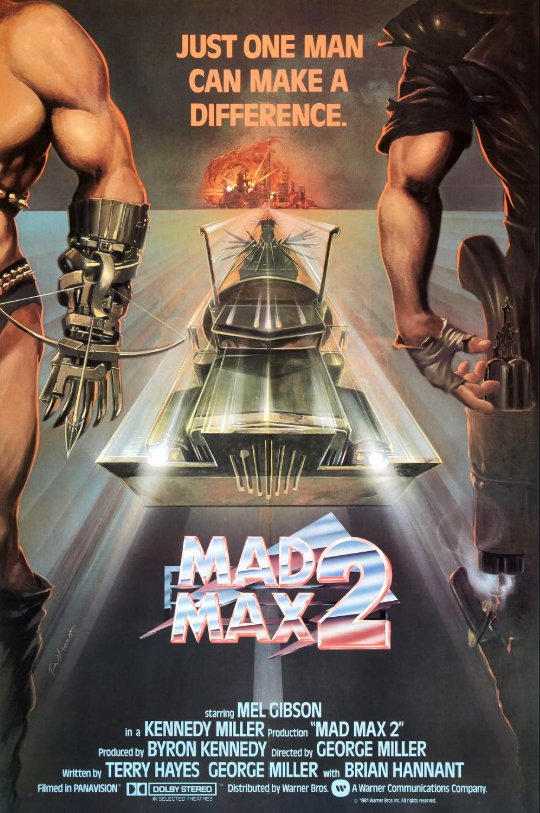

The only thing that kept me sane was movies. Fortunately, 1982 turned out to be the most incredible time in cinematic history to be a nerd. A string of classics came out that summer including Blade Runner, The Thing, The Road Warrior (a.k.a. Max Max II), Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, Poltergeist, Tron, Conan the Barbarian, and (the 800-pound gorilla) E.T. Even at the time, I was cognizant that this bumper crop of cool films, all coming out within a few weeks of each other, was a very unusual, almost magical development. I spent many hours on the bus with my friends going to and from the local cineplex, where we watched many of these films over and over.

For forty years, I labored under the delusion that this rapid series of classics was just a lucky coincidence. But while reading Chris Nashawaty’s fine nonfiction book, The Future Was Now: Madmen, Mavericks, and the Epic Sci-Fi Summer of 1982, I learned otherwise. A good historian will reveal that any event, no matter how seemingly incredible or unlikely, actually emerges logically from previous events. That is, the seeds were planted years or even decades before. And in 1982, main seed was a little film called Star Wars. As Nashawaty explains:

There’s an unwritten rule for reporters and trendwatchers who cover Hollywood that if you want to know why a movie—or a particular group of movies—was made, all you need to do is look back and see what was a hit at the box office five years earlier since that’s the typical gestation period for studio executives to spot a trend, develop and green-light an imitator, push it into production, and usher it into theaters. And the summer of 1982 would prove no exception, coming exactly five years after Star Wars. What seemed underreported, however, was how this new wave of sci-fi titles had been conceived and carried out. It is a wave that we’re still feeling the aftereffects of, for better and worse, today.

To give a sense of how revolutionary Star Wars was, and what great impact it had on the budding film-makers of the time, Nashawaty describes how Ridley Scott, who was contemplating making another historical drama after his critically praised but unsuccessful Napoleonic tale The Duelists, found himself completely blown away when he saw Star Wars at Grauman’s Chinese Theater in L.A…

Inside the exotic, shrine-like confines of the famous movie palace that dated back to the 1920s, Scott managed to hunt out one of the few remaining empty seats. Once there, he turned around and scanned the room. It was completely packed with giddy college students, hopped-up kids, and their equally hopped-up parents. Then the lights dimmed, and John Williams’s opening brass overture blasted like a call to adventure. What followed—George Lucas’s moving scroll of text—described an enthralling new world, one where good battled evil, a menagerie of alien species came and went as if they’d always existed, and cutting-edge special effects lived seamlessly side by side with the most old-fashioned of swashbuckling heroics. Scott felt the skin on his arms pebble like gooseflesh and the hair on the back of his neck stand up and salute. He recalls barely blinking for the next two hours, in fear of missing something on the screen. He was transported.

Scott immediately ditched his latest art-house project and started looking for a big, FX-driven pop-movie (preferably sci-fi) that might capture some of that Star Wars magic. That film would become 1979’s landmark horror flick Alien, which established Scott as “the Toscanini of Terror,” in Nashawaty’s phrase.

After the runaway success of Alien, Scott briefly worked on pre-production for a film adaptation of Frank Herbert’s Dune, but that project never came to fruition, in part because of Scott’s grief over the death of his older brother to cancer. Instead, Scott eventually settled on a project based on Philip K. Dick’s great sci-fi novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep (soon retitled as Blade Runner). The experience would push Scott, screenwriter Hampton Fancher, and the entire cast and crew to the breaking-point, physically and emotionally. At the end of the ordeal, they had created one of the greatest movies ever.

If this tale of “tortured-production-resulting-in-classic-film” sounds familiar, that’s because it has been repeated countless times. Many film historians have noted that “easy” film-shoots—those where the director stays on-schedule and under-budget and the actors and the crew all get along with each other swimmingly—almost invariably result in bad, boring movies. A lack of pain and conflict usually means that the artists are not stretching themselves creatively. Not taking chances. Conversely, on films where the director and actors are all passionately committed to creating something of artistic value, emotions are bound to run high. After all, everyone on such a shoot is being challenged—by the time-table, by the studio, by bleeding-edge technology, and by their own high standards.

Which brings me to the thing I like most about Nashawaty’s book: the way he relates the passion and struggles of all eight directors on these films. The mere fact that so many pop films came out that summer—exactly five years after Star Wars—is not so surprising. What is surprising is how much passion and energy was put into them. After all, they could have just been horrible knock-offs (ever see Battle Beyond the Stars?), but they weren’t. The were great, original, innovative films.

Besides Scott, the other director who seemed most driven to deliver his true artistic vision was George Miller. His first film, Mad Max, was an international smash but bombed in the U.S., mainly due to a botched release and also the stupid idea of dubbing the actors’ dialogue into American accents. So, Miller found himself wanting to not so much make the sequel as re-shoot the original film in the way he had envisioned, with a real budget and the support of an real studio.

The result was nothing short of mythic. As Miller explained at the time, Max Rockatansky is not just a tough-guy movie hero. He is an archetypal figure:

Here was an Australian genre picture that seems to have resonance all over the world. Like in Japan, for instance. I’d never seen a Kurosawa movie, yet the Japanese said Mad Max is a samurai movie and that’s why he’s successful in Japan. Someone from Iceland told me it’s exactly like the wandering loner in Viking folklore. I began, for the first time, to examine this process we call ‘storytelling.’ … Here was something a lot bigger than any individual—forces deep and mysterious that drive this need we have to tell each other stories. The person who shone the great floodlight on all this was Joseph Campbell.”

As most film-nerds already know, Joseph Campbell was the famous scholar whose writings inspired George Lucas to create Star Wars and, later, greatly influenced Hollywood screenwriting. Campbell’s most famous idea was the concept of the monomyth, the Hero Story whose basic pattern and structure is repeated over and over throughout world mythology. What Nashawaty does not explain—because he doesn’t need to—is that the Hero Story doesn’t just apply to many of the films that came out in 1982. It equally applies to the directors, producers, and actors, all of whom found themselves embarking on an epic journey full of danger and challenges, all in pursuit of the same boon—a great film.

If the filming of Blade Runner was stressful on its cast and crew, the shooting of The Road Warrior was literary bone-crushing. Stuntmen and actors were routinely injured while performing the spectacular stunts that became Miller’s trademark. But the other films from 1982 had their own challenges—less violent but just as real and agonizing. On the set of The Thing, John Carpenter was flying by the seat of his pants, relying on a young FX wizard named Rob Bottin to create the morphing-alien sequences. These, he hoped, would be completely original and frighteningly real. (They were.) And, of course, he was shooting in freezing weather.

For Star Trek: The Wrath of Kahn, director Nicholas Mayer and producer Harve Bennett (who had the idea of making the film a sequel to the original Space Seed episode from 1967) were battling the clock, crazed Trekker fan boys, the egos of the main actors, and, most of all, the knowledge that, should Wrath of Kahn fail to gel, it would be stinker #2 in the Star Trek film series, which would disappoint millions of fans (again) and kill the entire franchise (probably). The production for Poltergeist was plagued by (baseless) rumors that director Tobe Hooper (of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre fame) had been supplanted by producer Steven Spielberg. Similarly, pre-production for Conan the Barbarian was marred by in-fighting between original scriptwriter Oliver Stone (who believed he would also be directing the picture) and the actual director John Millius.

Naturally, The Future Was Now is a celebration of that great, shining moment in pop-cinema. But, as the title suggests, it also reveals how the promise of that long-ago summer went largely unrealized. The 1990s soon came, with the era of bloated would-be “blockbusters” that with budgets ballooning into the stratosphere and scripts so poorly written they might have been composed by a committee (or, these days, by AI). The emphasis on FX-driven blockbusters meant that each studio could only afford to make fewer and fewer films each year, and those movies had to be larded with so-called crowd-pleasers like gratuitous violence, wooden romance, vapid “humor,” etc. In fact, looking back on 1982, it seems miraculous that a gigantic art film like Blade Runner was ever made at all. It bombed at the box-office, after all, and the sequel would take thirty-five years to make (and it bombed, too).

Ultimately, rather than a celebration, The Future Was Now feels almost like a dirge for a by-gone, golden age. Or, rather, a golden summer, lasting just a couple of months—the moment when the nerds and their Peter Pan impulses, took over mass culture, for better or worse.

Check it out…

One thought on “What I’m Reading: “The Future Was Now””