I finally moved out of my parents’ house when I was twenty-two, when I embarked on a cross-country move to Tucson, Arizona. I had enrolled in an M.F.A. program at the university there, and I arrived knowing not a single, living soul. Once I found a place to live and acquired a U-of-A ID card, I spent my evenings going to the small, student gym in the basement of the football stadium, where I and a few other lonely souls (all dudes) worked out until the lights went off.

I vividly remember my first night at that gym. There were radio speakers in the ceiling tuned to the local F.M. rock station. That night, as it happened to be running an hour-long special devoted entirely to one rock album: Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours. The show included a few tracks off the album along with interviews with Lindsey Buckingham, Stevie Nicks, and Christine McVie. (For some reason, Mick Fleetwood and John McVie were left out.)

By this time, Rumours had already achieved legendary status of the sort afforded very few pop-music albums. (Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band is perhaps the only other.) Today, many years after that first night in Tucson, the album’s popularity and reputation has not diminished. If anything, it has increased. It’s gone from being a recognized artistic masterpiece to a timeless cultural colossus. As each new generation of music fans and musicians have discovered Rumours, an entire legendarium has been constructed around it.

Entire books have been devoted to the months-long, tortuous period in 1977 when the album was recorded. Two of the band’s members, John and Christine McVie, were in the midst of an ugly divorce. Two other members, Stevie Nicks and Lindsey Buckingham, were in the midst of an ugly breakup. And the remaining member, drummer and band leader Mick Fleetwood, was on the verge of breaking up with his famous wife, Jenny Boyd. The five members alternated between screaming obscenities at each other and slipping into effortless, soulful harmonies, all while drinking heavily and vacuuming titanic amounts of cocaine up their collective nose.

At one point late in the process, the album’s producer, Ken Caillat, was horrified to discover that the master recording tapes were literally flaking-out. They had been re-run through the mixing machines so many times that the metal-oxide strip was coming loose from the plastic, threatening to lose all the work he and the band had done. A technician from the manufacturer was flown in to manually transfer the recording onto a new tape before disaster struck.

In short, the fact that Rumours was made at all seems like something of a miracle.

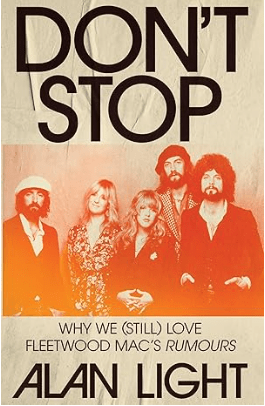

In his excellent book, Don’t Stop: Why We Still Love Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours, cultural historian Alan Light covers all this history only lightly, which is good because others (including Caillat himself) have already gone over that ground. Light’s real focus is the album’s enduring (and increasing) cultural impact. Cleverly divided into one-song-per-chapter, the book serves as a kind of journey through the track listing, explaining the origins of each song. Even better, it explores the reactions of people at the time of the album’s release, in the decades since, and right up to the present moment. One of my favorite passages quotes modern-day music producer Michael Ozowuru:

[Ozowuru] has worked with [Frank] Ocean, as well as Beyoncé, SZA, and Rosalía. As a teenager in California, his musical obsessions were Stevie Wonder, OutKast, A Tribe Called Quest, and Fleetwood Mac. “At the time, I listened to a lot of rap music,” he says, “but something about the sonics of Rumours lends itself to the sonics of rap or present-day pop—something about the crispness and the energy around it. The bass, and the relation of drum and bass, feels very contemporary. I don’t know how they did it, but however they were getting the bass to sit with the drum tones is, to me, very hip-hop. The DNA from this music has probably been in more hip-hop and more pop music than we realize, just by proxy of how great they got those sounds to sound back then.”

Many other current musicians, podcasters, and influencers are also quoted. Light’s achievement is the way he organizes these quotes into a pattern, one that not only enumerates Rumours’ otherworldly magic, but conducts it to the reader. As with any great work of criticism, Don’t Stop re-ignites our interest in the subject—and, somehow, amplifies it.

He makes it come alive. Again.

All of these moving, heart-felt reactions serve to get at an aspect of Rumours that most critics miss. Namely, its almost sublime, ineffable quality, which no one—not Light, nor Caillat, nor the bandmembers themselves—can explain or even adequately describe. The music just works. It hits on such a deep, almost primal level that many people (myself included) can remember the first time we heard one of the songs. For me, it was the day when I heard “You Make Loving Fun” by Christine McVie. I was driving into the parking lot of the small college where I worked, and I sat in the car just listening, completely lost in the music, its layers and voices and currents. It was amazing.

So amazing, in fact, I have a weird, crackpot theory about Rumours. I believe in an afterlife. In a heaven, of some form. And this heaven is a lot like Earth, only better. Everything there is a thousand times better. Food. Movies. Weather. Sex.

And music, of course.

I also believe that, once in a great while, we mortals down on Earth get a little sneak peak of the music of heaven (or the food, or the movies, etc.). Rumours is one of those sneak-peeks.

As Light’s title suggests, however, his book is not just concerned with how amazing Rumours is as a work of art. He also attempts to explain that ineffable quality I alluded to above. The matter of what, exactly, makes Rumours so great.

For me, the obvious answer lies in something that scientists call hybrid vigor. This is the positive effect one gets when cross-breeding individuals from very different gene pools. The offspring often display increased health, fertility, size, growth rates, etc. My favorite example of this phenomenon comes from the true-life story of the mutiny of the H.M.S. Bounty. The mutineers from the ill-fated ship ended up on a tiny island in the South Pacific, where they interbred with locals. A few generations later, when studied by anthropologists, the descendants of these English sailors and Polynesians women were found to have better teeth, muscle tone, resistance to disease, and longer life.

In other words, variety brings advantages. And the greater the variety, the greater the advantages.

The same kind of thing happened, I think, with Fleetwood Mac, albeit in an artistic instead of biological sense. Originally a blues band in England, Fleetwood Mac had already undergone several incarnations by the time it relocated to the U.S. in the mid 1970s. It was blind luck (or perhaps fate) that brought the core members—Fleetwood, John McVie, and Christine McVie—to Los Angeles, where Fleetwood fatefully heard Lindsey Buckingham playing guitar. Buckingham was recording tracks for the latest album from Buckingham Nicks, the duo he had formed with his college girlfriend Stevie Nicks. (One could write a whole other essay on the fatefulness of that pairing, but never mind.) Fleetwood was so impressed with Buckingham’s artistry that he immediately offered him a place in the band. Buckingham agreed, on the condition that Nicks also be allowed to join. Fleetwood assented, and thus began the greatest hybridization in rock history. As Light recounts:

Merging three Brits who had been playing for almost a decade and survived numerous disasters, musical and otherwise, with two Californians who had a very different vocabulary, musical and otherwise, was never going to be easy. Buckingham sensed a dynamic that, in some ways, would never change for the group. “Three English people and two Americans, there’s just cultural differences,” he said to Joe Smith. “There’s been a certain distance, I would say, and in the least negative sense that I could put it, to where we’ve only gotten to know each other as friends to a certain point… There was a formality there, in that sense, always and still is.”

And there was another kind of hybridization at work in the band, one that remains surprisingly rare in the rock world. Namely, the combination of men and women. Light describes this dynamic as follows:

Rolling Stone’s Dave Marsh tried to make sense of the album’s commercial explosion. He noted that Fleetwood Mac was “the first successful rock group since the Mamas and the Papas to fully incorporate women into their creative framework… Fleetwood Mac may speak more clearly than anything else to an audience that’s been through similar problems.”

It was this blending of different backgrounds, perspectives, and discourses—British and American, male and female, blues and folk—that somehow, improbably, came together in perfect harmony, and created one of the most original and creative masterpieces of the 20th Century.

And there is another reason, I think, Rumours is so enduringly great. It has to do, indirectly, with the incredible conflict and psychological stress that the bandmembers underwent while recording the album. Rumours is full of emotional points and counter-points, actions and reactions, especially between Buckingham and Nicks. It is perhaps the greatest meditation on the pain of breaking-up, as well as on the joy and hope of moving on.

The paradox of Rumours is that, because of all this angst and turmoil, the band’s members were actually drawn closer together, as artists if not as lovers. One feels that, by the time the album was finished, the five members were greater friends, in some ways, than they were before.

And it shows. Each member brings out the best in the other members (along with a lot of rage and angst.) As Light quotes one close confidant: “They always added so much beauty to each other’s songs, even when they were ripping each other to shreds.”

Simply put, Rumours works so well because the members loved each other, and were fully committed to the art they were making. Five great artists—three brilliant singer/songwriters, two world-class bluesmen—coming together to make a work of genius.