I find it interesting that the two most famous architects in American history—famous, that is, among ordinary people who don’t subscribe to Architectural Digest—were both named Frank. They were, of course, Frank Lloyd Wright and Frank Gehry. Both men created buildings that captured the popular imagination like few others. And both were mavericks whose vision of what architecture could do often offended the mavens of the status quo (not to mention the bean-counters who worked for the rich people who funded their projects).

Both men also shared a sense of play and in their work—Gehry to a much greater degree, sometimes designing homes and offices and other buildings that veered into pure fantasy. He often brainstormed new projects with strips of paper and cardboard, envisioning light, fluid, soaring structures that, one could argue, would not have been possible to actually build in an age before computer-assisted design was available.

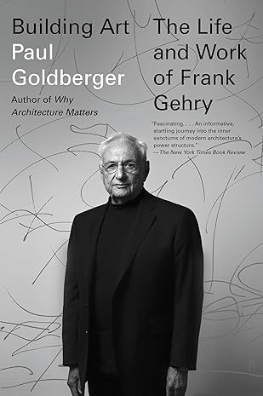

This emphasis on play and the power of imagination was evident in all his work, even in huge, civic projects like his Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles. As Paul Goldberger relates in his fine biography, Building Art: The Life and Work of Frank Gehry, Gehry took an almost impish pleasure in fooling around with his own designs. When he was in the early stages of mocking-up his plans for another auditorium in Asia, he shocked and amazed his colleagues by adjusting the position for the auditorium every night or so. As one friend put it,

…[H]e became a monster. He started moving stuff around.… We were doing a project in Korea that never got built [the museum for Samsung] but every time I went on a trip and came back he had moved the auditorium. He was impeccable. He had incredible reasons for it. He’s really brilliant. He doesn’t sleep at night and he comes back the next morning and moves the auditorium.”

As Goldberger explains…

Moving the auditorium, in Frank’s view, was a form of what he liked to call “play,” and it was largely instinctive. “A serious CEO, you would imagine, does not think of creative spirit as play. And yet it is,” he said. “Creativity, the way I characterize it, is that you’re searching for something. You have a goal. You’re not sure where it’s going. So when I meet with my people and start thinking and making models and stuff, it is like play.”

As the title of Goldberger’s book relates, Gehry saw himself almost as more an artist than an architect. At times, he refused to believe that one needed, necessarily, to make a distinction between the two. Early in his career, Gehry befriended and hung-out with great modern artists in Southern California, and they reciprocated his admiration. Perhaps this is the reason that Gehry’s greatest buildings resemble art more than perhaps other architect.

His most famous is, of course, the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain. When the museum finally opened in 1987, a flood of tourists came from all over the world to see it, prompting some of the artists whose work was displayed inside the museum to feel that they were playing second fiddle to the building itself. This grumbling grew into a modest backlash among the artistic community, focused not so much on Gehry himself as on the fawning admiration of journalists and other architects who often lauded Gehry as an “artist.” As Gehry’s own collaborator and friend, the sculptor Richard Serra, said,

I don’t believe Frank is an artist. I don’t believe Rem Koolhaas is an artist. Sure, there are comparable overlaps in the language between sculpture and architecture, between painting and architecture. There are overlaps between all kinds of human activities. But there are also differences that have gone on for centuries.”

Whether he was being lauded or criticized, Gehry himself never seemed concerned. In fact, when compared to that other great architect named Frank, Gehry usually seemed downright humble, if not pathologically shy. Goldberger writes:

Even though Gehry was ridden with angst throughout his life, his manner came off as relaxed, low-key, and amiable, and his steely determination, far from being obvious like Wright’s, was hidden behind an easygoing exterior, a kind of “aw shucks” air that Gehry’s old friend the artist Peter Alexander called “his gentle, humble ways.” Wright was never mistaken for being modest; Gehry often was.

Gehry was so shy, in fact, that I feel he could have been much more famous than he was if he gotten himself out there, gone on TV more and granted more interviews and written some puff-pieces for various magazines and web sites. The fact that he did not is, I suppose, the most telling fact about the man’s character. Namely, that he was a genius who was determined to create the most original and uplifting works as he could…and, then, to let those works speak for themselves.

Godspeed, Mr. Gehrey….