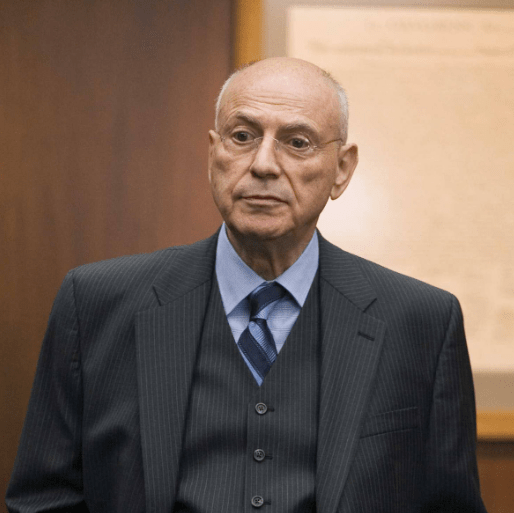

Like millions of others, my family and I have spent part of this year’s Christmas holiday watching some version of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. Actually, we watched two, starting with Bill Murray’s mad-cap Scrooged and following-up with a much darker made-for-TV film from 1999, starring Patrick Stewart. The production was inspired, in part, by Stewart’s one-man stage performances as the character, and Stuart gives a powerful, tragic interpretation of Scrooge, a man so consumed by his traumatic past that he is unable to experience any emotion other than anger, manifested as a chronic, toxic misanthropy.

A Christmas Carol is, of course, an unabashed Christian parable, perhaps the most influential in history outside the Bible itself. Scrooge is visited by ghosts over three nights (the same number as Christ lays dead in his crypt), until his “resurrection” on Christmas morning, having seen the error of his ways. But the story resonates with people of all faiths, or no faiths, because of its theme of hope. Scrooge is old, but he ain’t dead yet. There’s still time to fix his life. To change. To choose.

I have always thought that the power to choose–the divine gift of free will–lies at the heart of A Christmas Carol, as it does with all great literature. Of course, it’s hard to imagine Scrooge, after seeing the tragedies of his Christmases past, present, and future, to wake up on Christmas and say, “Meh, I’d rather keep being a ruthless businessman. Screw Tiny Tim.” But he could. He might. The ultimate choice given to us is the option to change the nature of our own hearts, our way of thinking.

This matter of free will seems particularly salient this year–this holiday season–because the very concept is under attack. If you Google the term “free will,” you will be presented with a barrage of links with titles like “Is Free Will an Illusion?” and “Is Free Will Compatible with Modern Physics?” Along with the rise of militant atheists like Richard Dawkins, a parallel trend has arisen among theoretical physicists who doubt that free will is even a meaningful concept. After all, if our consciousness is merely an emergent phenomenon of electrical impulses in our brains, and if our brains are, like everything else, determined by the laws of physics, then how is free will even a thing? Every idea we have—every notion—must somehow be predetermined by the notions that came before it, the action and reaction of synapses in our brains.

Our brains, in other words, are like computers. Mere calculators, whose order of operations could be rewound at any moment and replayed again and again and again, with exactly the same results.

Ah, but what about quantum mechanics, you say? The principles that undergird all of quantum theory would seem to imply that human thought, even if you reduce it to electrons in the brain, might be on some level unpredictable, unknowable, and therefore capable of some aspect of free will. Not at all, reply the physicists. The scale at which Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle applies—the level of single electrons and other subatomic particles—lies so far below that of the electrochemical reactions in the human brain that their effect must be negligible. That is, a brain with an identical layout of neurons to mine would have exactly the same thoughts, the same personality, as I do. It would be me.

It’s this kind of reasoning that leads people to hate scientists at times, even people like me who normally worship scientists. The arrogance of the so-called “rationalist” argument—which comes primarily from physics, a field that, in the early 1990s, discovered that it could only explain 4% of everything in the universe—seems insufferable. But more to the point, I would argue that the rationalist rejection of free will leads to paradoxes—logical absurdities—not unlike those created by the time-travel thought problems that Einstein postulated over a hundred years ago.

For instance, imagine that one of our free-will denying physicists wins the Nobel Prize. He flies to Stockholm to pick up his award, at which point the King of Sweden says, “Not so fast, bub. You don’t really deserve any praise, because all of your discoveries were the inevitable consequence of the electrical impulses in your brain.”

“But what about all the hard work I put in?” the physicist sputters. “All the late nights in the lab? The leaps of intuition that came to me after countless hours of struggle?”

“Irrelevant,” says His Majesty. “You did all that work because your brain forced you too. Your thirst for knowledge, and also your fear of failure, were both manifestations of mechanicals in your brain. You had absolutely no choice in the matter.”

“Well, in that case,” replies the now angry physicist, “maybe YOU have no choice but to give me the award anyway, regardless.”

“Hmm,” muses the King. “I hadn’t thought of that.”

“So, can I have it?”

“I dunno. Let’s just stand here a minute and see what happens.”

As many critics have pointed out, this kind of materialist thinking inevitably leads to a kind of fatalism of the sort found in some eastern religions. If human beings really have no free will—that is, if we are basically automata in thrall to the physical activity of our brains—then what’s the use of struggle? Why bother trying to improve yourself, to become a productive member of society, or become a better person?

Straw man! scream the physicists. No one is advocating we give up the struggle to lead better lives. That would be the end of civilization. No, we simply mean that this struggle is an illusion, albeit one that we need to exist.

Okay. So, you’re saying that we all have to pretend to have free will in order to keep the trains running? We must maintain the illusion of free will in order to continue the orderly procession of existence? But doesn’t this position, itself, imply a kind of choice? After all, if we have no free will, it really makes no difference whether we maintain the illusion or not.

Doesn’t this very discussion represent a rejection of passivity and the meaningfulness of human will?

My fear is that many young people today will be overexposed to the “rationalism” I describe above, especially when it is put forth by otherwise brilliant people. For those who are already depressed by such assertions that free will is an illusion, I would direct you to the great stories of world history. All the enduring mythologies, from the Greek tragedies to the Arthurian legends to the Hindu Mahabharata, revolve around the choices made by their heroes, their triumphs and failings. As a fiction writer, I would argue that the concept of “story” itself is almost synonymous with choice. A boy is confronted by the wolf. Will the boy run left or right? Will he lead the wolf away from his friends back at the campsite, or will he lead the wolf to them, hoping they can help scare it away (or, more darkly, that it will eat one of his friends instead)?

One can also take hope in the fact that not only can physicists still not explain what 96% of the universe is but they can’t explain what consciousness is. Of course, some would argue that consciousness, itself, is an illusion. But this leads to an entirely new set of paradoxes and absurdities. (As David Bentley Hart once replied, “An illusion in what?”)

Personally, I suspect that consciousness comes to exist around or about the same moment in a specie’s evolution when the individual can choose. That is, consciousness implies a kind of choice. It might be a very elemental, even primal kind of choice—perhaps simply the choice of whether not to swim harder, or fight harder, which I believe even minnows and ants can make—but it’s still a choice, and not merely a matter of pure instinct.

One of my favorite TV shows from my childhood was Patrick McGoohan’s “The Prisoner”, whose every episode begins with the titular character proclaiming “I am not a number! I am a free man!” This assertion, shouted on a beach by the mysterious village in which he has been imprisoned, is followed by the sinister laughter of Number 2, the Orwellian figure who has been tasked with breaking the prisoner’s will. Number 2 is, of course, an awesome and terrifying figure, armed with all the weapons of modern society: technology, bureaucracy, and theory. But he’s still wrong, and he’s ultimately unable to grind the prisoner down.

That’s the hope I cling to, the Christmas message I espouse. Namely, that we’re all able to choose to resist the fatalism of rational materialism. That we can all, eventually, escape the village and be better human beings.

Anyway, that’s my Christmas Eve rant.

(Author’s Note: this is an updated version of a post that originally appeared on my old blog, Bakhtin’s Cigarettes.)