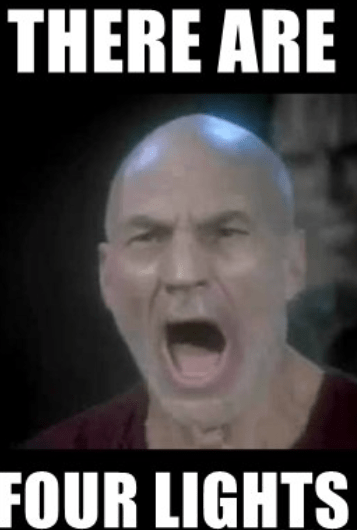

It is almost a law of nature that if you scroll through Twitter for long enough, you will run across a Star Trek meme. And, if you keep scrolling, you will eventually run into a “There are four lights!” meme.

These memes are, of course, a reference to one of the most famous episodes of Star Trek: The Next Generation. Entitled “Chain of Command,” it depicts the ordeal that Captain Picard must endure at the hands of a Cardassian interrogator named Gul Madred. It is one of the most famous (infamous?) episodes because of its brutal depiction of torture and humiliation, up to and including the truly shocking moment when Picard is hung naked by his wrists (thus cinematically immortalizing Patrick Stewart’s impressively muscular British arse). Despite the disturbing subject—or, perhaps, because of it—the episode has become one of the most beloved and acclaimed of the entire series.

I, for one, believe that “Chain of Command” deserves every iota of the praise it has received. It’s brilliantly acted, of course, by Stewart and his former Shakespearean colleague David Warner, who was one of the greatest actors of his generation. And it tackles a dreadful but important subject—the nature of political torture. Screenwriter Frank Abatemarco conducted research into the impact and nature of such torture as reported by Amnesty International, and the episode seems completely believable, not to mention chilling. It dissects the psychology of the victim but also of the torturer, with Warner brilliantly conveying how Madred, an intelligent man and, apparently, a loving father, is nonetheless able to rationalize his activities by dehumanizing his victim.

If one trawls the many Reddit threads and other chat-board threads that have been devoted to the episode, one learns that many of its fans—especially those former English majors, like myself—were quick to seize on its central homage to George Orwell’s 1984. Specifically, it echoes the climactic scenes in 1984 when Winston Smith is tortured by O’Brien, a man whom Winston believes to be a friend and fellow-revolutionary but who turns out to be a commander of the Thought Police.

As every Star Trek nerd knows, of course, the most direct parallel between 1984 and “Chain of Command” comes in the episode’s climax, when Madred shines four lights on the wall and asks Picard how many lights he sees. When Picard answers, truthfully, “four,” Madred shocks him.

In 1984, O’Brien lays Winston out on an electronic torture-rack and says to him,

“Do you remember,” he went on, “writing in your diary, ‘Freedom is the freedom to say that two plus two make four?”

“Yes,” said Winston.

O’Brien held up his left hand, its back toward Winston, with the thumb hidden and the four fingers extended.

“How many fingers am I holding up, Winston?”

“Four.”

“And if the Party says that it is not four but five—then how many?”

“Four.”

The word ended in a gasp of pain.

The torment continues, with Winston replying “five” and “three” and anything else he can think of to stop the pain. At which point O’Brien pauses the interrogation and says, “Sometimes, Winston. Sometimes they are five. Sometimes they are three. Sometimes they are all of them at once. You must try harder. It is not easy to become sane.”

It’s this portion of 1984 that, to me, establishes O’Brien as the supreme villain of world literature. He is also its greatest nihilist. He seems to have no illusions about the purpose of Big Brother’s totalitarian rule—namely, for the rulers to partake of the ultimate sadistic pleasure in endlessly tormenting their subjects, forever. He blithely explains to Winston how the state will soon make things even worse for the common people, including modifying human anatomy so that people cannot even have orgasms. When O’Brien also suggests that the state might increase the pace of life so that people go senile at thirty, Winston pleads:

“Somehow you will fail. Something will defeat you. Life will defeat you.”

“We control life, Winston, at all its levels. You are imagining that there is something called human nature which will be outraged by what we do and will turn against us. But we create human nature. Men are infinitely malleable.”

Many dudes on Reddit have observed, correctly, that the scene with Picard and Madred are about mind control, and how strong people must fight to resist it. But the greater issue comes in the last scene of “Chain of Command,” after Picard has been freed and is safely back on the Enterprise. There, washed and fed, he meets with Counselor Troy and explains the worst part of his ordeal—namely that, in the delirium of his agony, he actually saw “five lights,” as he was commanded to do by Madred.

In other words, despite his great intellect and courage, Picard’s body began to alter his perceptions. He became, in O’Brien’s words, “infinitely malleable.”

In 1984, Winston experiences the same horrific revelation.

And he did see them, for a fleeting instant, before the scenery of his mind changed. He saw five fingers, and there was no deformity. Then everything was normal again, and the old fear, the hatred, and the bewilderment came crowding back again. But there had been a moment—he did not know how long, thirty seconds, perhaps—of luminous certainty, when each new suggestion of O’Brien’s had filled up a patch of emptiness and become absolute truth, and when two and two could have been three as easily as five, if that were what was needed. It had faded out before O’Brien had dropped his hand; but though he could not recapture it, he could remember it, as one remembers a vivid experience at some remote period of one’s life when one was in effect a different person.

I have written before about how the greatest themes in literature are best posed as questions. The question here is, “Is there really some indominable spirit in us that can’t be crushed and mastered by force and torture?” Or, put another way, “Are human beings really infinitely malleable, to the point that they can’t even trust their own senses?”

To many—and especially to those who adhere to a philosophy of materialism—this might seem a banal question. Their answer would certainly be: Of course, people are infinitely malleable; human beings are the product of their sensations, and if those sensations can be completely controlled (through drugs or torture or propaganda), then those beings can be complete controlled, too.

If this is true, I fear that the future of humanity is hopeless. We will, eventually, devolve into some kind of hive-mind existence (yes, rather like the Borg in Star Trek), which, even if it isn’t quite as hellish as the nightmare-state that O’Brien creates for the proles of 1984, would still be devoid of individuality or any authentic human experience.

Fortunately, I don’t believe it is true. For one thing, as a practical matter, I don’t believe that a ruling class whose only motivation is sadistic sexual pleasure could sustain itself. It’s too destructive, and its members would inevitably turn on each other. And even if they didn’t, they would die out, unable to create and nurture the most basic form of life—children. In other words, Big Brother can only destroy. It cannot create.

On a more philosophical note, I do believe that there is a “something called human nature,” as O’Brien puts it, that will inevitably rebel against tyranny. All the hero stories of world mythology reflect this, as do our own, modern mythologies. Like, for instance, Star Trek. Clearly, in the imagined universe of the twenty-fourth century, civilization has not devolved into some kind of soul-destroying dystopia. Quite the opposite. The Federation represents civilizations response to the ever-present threat of oppression, in all its forms, from fascist militarism (the Klingons), xenophobic isolationism (the Romulans), to full-on, cybernetic collectivism (the Borg). The Federation beats them all.

So, what is the Federation’s secret? Probably a lot of things. But, for my money, it’s that the Federation is a pluralistic society, open to all races, ideas, and voices.

Back in college, I studied the great Russian literary critic M. M. Bakhtin, who saw the greatest innovation in art as the novel. The novel represents a quantum leap in art because it is the greatest example of what Bakhtin called dialogism—the interplay of voices and perceptions from which our shared experience of consciousness emerges. This impulse toward dialogism—dialogue—is always set in opposition to the evil but omnipresent forces of monologism, which strive to establish a singular, monolithic truth on humanity and thus control it.

Big Brother’s IngSoc party might be the most monologic literary creation ever imagined by a writer (Orwell). Conversely, the Federation might be the most dialogic, combining not only an endless multiple of voices and point-of-view but actual sentient species from all over the galaxy, united by there shared…humanity? For lack of a better word, yes.

Let’s hope Star Trek’s vision of the future is the one that plays out.