Most of the art I’ve included in my on-going Classic Sci-Fi Book Covers series has been from the 1970s and 1980s. Two golden ages of sci-fi, surely, which, more importantly, marked my golden age of sci-fi—my middle- and high-school years when I devoured all kinds of science fiction novels from the previous decades.

And so it is with some surprise that I submit this episode’s sci-fi cover, which is only from 1998. But it’s still a classic. An instant classic, actually, and not just because it was done for one of the most influential sci-fi novels of all time, Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? Calling PKD a science fiction writer makes a bit more sense that calling Kurt Vonnegut a science fiction writer, or Franz Kafka a science fiction writer, but not much. Like Vonnegut and Kafka, Dick wrote surreal, even psychedelic novels that deal with issues of compassion, violence, identity, sanity. Most of all, they describe the problem of discerning reality from the fake. (The “ersatz,” as Dick likes to call it in his typical Germanophilic style).

Do Androids Believe in Electric Sheep is Dick’s most famous book, in part because it inspired Blade Runner but also because it’s just a fine, complex, and vivid novel. Rick Deckert, the protagonist, is a bounty hunter who finds and kills runaway androids (called replicants in the film, these are flesh-based artificial people who look and act like human beings, only crueler.)

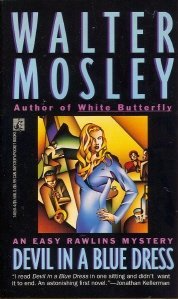

The book was published in 1968 and has gone through dozens of editions and covers. But this cover, created by commercial artist Bruce Jensen, is my favorite. It depicts a male figure who might be a Greek statue, or a wax dummy (or an android), and yet whose expression conveys a sense of pathos that the viewer can’t quite look away from. This sense of pathos is amplified by the fact that lying between the viewer and the figure is a grid of what seems to be hog-wire, evoking a plot point in the book. Deckert, like many people in his dystopian future, keeps a farm animal as a pet—in his case, a sheep. But the wire also has echoes of the Holocaust, which is especially interesting since Dick’s inspiration for the book came after reading the diary of an S.S. Officer guarding a concentration camp. The figure is, we sense, a prisoner, although we don’t know what of. (Spoiler: it’s modern civilization.)

And then there is the sheep itself, rendered in a hallucinogenic little box over the male figure’s left eye. The only point of color in the work, the sheep draws the viewer’s attention the same way Deckert’s sheep draws out his latent humanity—it represents nature, vitality, warmth. Most importantly, it serves as something to love.

Love, as it turns out, is the last human quality that the androids learn (and most never do). It is also, Dick strongly suggests, the defining aspect of living things.