Have you ever noticed that, at any given time, the tech bros and sci-fi nerds of the world are obsessed with one current, real-world technology. Right now, it’s AI. A few years ago, it was cryptocurrency. The topic itself changes over time, but whatever it is, they can’t stop talking about it.

I’m a bit of a nerd myself, but I must confess that I was never much intrigued by cryptocurrency, and I am only mildly interested in AI. Rather, my technological obsession is the same as it was when I was in high school: controlled fusion energy, a.k.a. fusion.

Fusion was a staple of almost every sci-fi book of the 1970s and ‘80s in which space travel or future civilization was described. Heck, even Star Trek’s U.S.S. Enterprise uses fusion to power its impulse engines. That’s why nerds of a certain age were so bewitched by the idea, and we still are.

But the idea itself isn’t science fiction—at least, not for much longer.

Fusion’s potential as the ultimate, clean power source has been understood since the 1940s. The required fuel is ubiquitous (basically water), the radioactive waste negligible (much lower volume and shorter-lived than fission waste), the risk of a meltdown non-existent (uncontrolled fusion reactions don’t ramp-up; they snuff-out), and the maximum power potential unlimited (fusion literally powers the stars).

The very idea of a world powered by clean, cheap fusion energy is enough to make a nerd’s eyes twinkle. (Well, this nerd, anyway.) No more oil wars. Fossil fuels would be worthless. We could use all the extra power for next-gen construction, manufacturing, water desalination, enhanced food production, and on and on and on. Best of all, we could start actively removing all the CO2 that we’ve been pumping into the earth’s atmosphere for 300 years.

Of course, a good bit of that power windfall will probably go to AI data centers, whose appetite for energy seems insatiable. And growing. Whatever your feelings are regarding the AI revolution, it is going to be one of the most important, disruptive, and consequential developments of human history, second only to the invention of the digital computer.

We’ll need fusion to power it.

So, I find it pleasingly ironic that AI might turn out to play a role in the mastery of fusion energy itself. I learned of this from an article on the World Economic Forum’s website, entitled “How AI will help get fusion from the lab to the grid by the 2030s”. To grasp the gist of the article, however, one should first understand how incredibly, maddeningly, ridiculously difficult controlled fusion is.

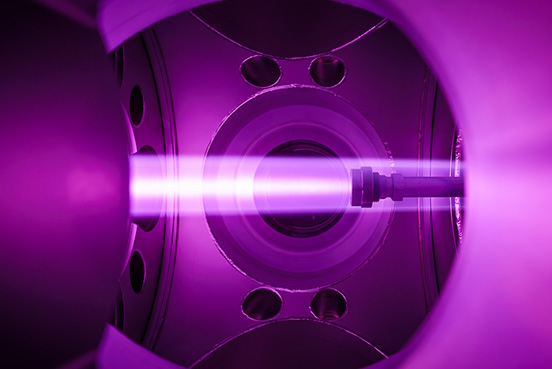

Fusion works by pressing atoms (of hydrogen, usually) together at enormous pressure—so enormous that it can overcome the mutual repulsion of these atoms and cause them to fuse and form a bigger atom (helium), while “sweating” a photon or two in the process.

This photon sweat is the bounty of the fusion energy, and it’s YUGE. Unfortunately, the process of squeezing a hydrogen plasma into a tight enough space for a long enough period of time at millions of degrees Celsius, without it leaking out the side or, worse, squirting off into the walls of your reactor and melting everything, is damned hard. You remember those prank spring snakes that pop out of a can when you open a lid? Imagine cramming a billion of those snakes into a can the size of a thimble and you’ll have some idea of the challenge.

Taming a fusion plasma is so hard, in fact, that it well be one of those hyper-intensive tasks mere human beings—with our leaden reflexes, sluggishly throwing switches and pushing buttons—might not be able to manage.

For an analogy, I often think of the F-117 Nighthawk, the first true “stealth” bomber produced back in the 1980s. The Nighthawk didn’t look like a regular airplane because it wasn’t a regular airplane. Rather, the distinctive, saw-tooth pattern of its wings and fuselage, which was the essence of its radar-evading design, made it look ungainly. And, indeed, it was ungainly, so much so that no human pilot could fly it unaided. Instead, an on-board computer was required to make constant corrections, microsecond by microsecond, to keep the plane in the air and on target.

Controlling a nuclear plasma is, I suspect, a lot like flying a stealth-bomber; constant corrections are needed to keep the fluid stable. And they need to happen much faster than a human being can comprehend, no less attend to.

Enter AI.

As we all should know by now, you can teach an AI how to do almost anything—including (we hope) how to maintain a fusion plasma. As the article I mentioned above explains, a partnership has been created between the private company Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS) and AI research company Google DeepMind to do just that. One of the more notable achievements of this partnership so far is the creation of a fusion plasma simulator called TORAX, which could be used to train an AI.

Of course, I have no idea if this partnership will turn out to be fruitful. For that matter, I have no idea if we will ever, truly, crack the fusion code once and for all. But I think we will. And I’m not alone. As one expert, Jean Paul Allain, states in the article, “Fusion is real, near and ready for coordinated action.” In other words, fusion might soon be a real thing. For this reason, capitalists have caught the fusion bug and are funding dozens, if not hundreds, of related start-ups, including CFS.

In some ways, this fusion mania is reminiscent of the very earliest days of aviation (way earlier than the Nighthawk). Back in 1908 or so, there were literally hundreds of amateur aviators in Europe, desperately trying to master the trick of powered flight. Many of these enthusiasts were smart, self-funded, and brave. But their craft were not much better than cannonballs with wings, unable to turn or steer, or even stay in the air for very long. Sure, they had all heard rumors of a possible breakthrough that might have been achieved by those bicycle-shop boys, the Wright brothers, over in the U.S., but no one knew exactly what had happened. And they certainly hadn’t seen the proof.

Then, on August 8, 1908, Wilbur Wright brought the proof.

At an exhibition in Le Mans, France, Wilbur flew his and Orville’s latest model over the famous racecourse, remaining in-flight for a full one minute and 45 seconds. More important than the duration, though, was the fact that he could steer the airplane, demonstrating banked turns, climbs, and dives.

Three years later, he flew a newer model over the same racecourse for 31 minutes and 25 seconds.

The world had changed.

The same kind of progression is now happening in fusion. In 2024, Korea’s KSTAR tokamak sustained plasma for 102 seconds. In February of 2025, the WEST in France sustained a plasma for 22 minutes. Each year or so, the record gets longer, and the plasma becomes more stable. And all this is happening before the ITER mega-reactor has even come on-line (as it is expected to do this year).

One of these days, fusion is going to take off and never land.

And the world will change. Again.