When I was an English major at the University of Florida, one of the best classes I took was a Survey of Science Fiction Literature course. It covered a lot of famous American and British SF, some of which I had already read as a teenager and some of which were new to me.

Looking back on it now, it occurs to me that two of the writers we read in the class were not only totally different from each other, they also presented two completely opposite visions of what we now call artificial intelligence. These writers were Isaac Asimov and Harlan Ellison.

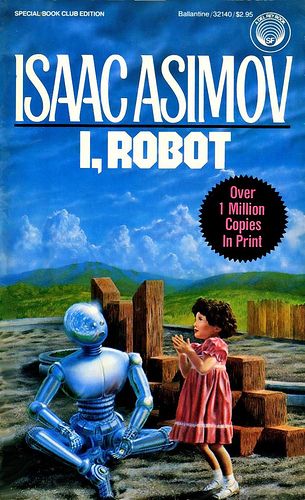

For Asimov, we read his early, seminal work, I, Robot. This is the short story collection that included his first formulation of the Three Laws of Robotics, which have been alluded to (i.e, ripped off) in countless other science fiction stories, including Star Trek. The book came out before the term AI became common parlance. Yet, in Asimov’s imagined future, the world is rife with robots that are essentially AIs with mechanical bodies. All of them have positronic brains (yeah, Star Trek ripped off this conceit, too) with the Three Laws hard-wired in. The result is that all robots function as humanity’s tireless, benevolent servants. (Some would say, slaves.)

Actually, they are much more than that. They can think, reason, and make choices. In fact, they have to make choices. The moral dilemmas created by the Three Laws as the robots interact with chaotic (and often evil) human beings is the source of drama in most of the stories.

Despite the mystery and drama of the stories, though, Asimov’s vision is a very optimistic, almost Buck-Rogers-esque idea of the future—not quite a utopia but close to it. There is no poverty, no hunger, no war. It’s only upon close reading of the stories in I, Robot that the exact nature of the master/servant relationship between humans and robots appears fraught—probably more so than Asimov consciously intended. This is especially true in a few of the stories, where it’s revealed that future governments are secretly run by the highest order of HAL 9000 style robots, whose plans might be beyond human comprehension.

Later in the Science Fiction class, we read Harlan Ellison’s short story “I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream,” which is quite possibly the darkest and most disturbing short story I have ever read, sci-fi or otherwise. And, of course, it involves an AI.

The story is mostly set underground, about one hundred years after a nuclear war wiped out all of humanity except for five people. The war was started by a mutinous Pentagon computer (yeah, just like Skynet) called AM that becomes self-aware and decides it hates human beings more than anything. After killing everyone on the planet, it preserves the five people as its playthings, running them through an endless number of elaborate, sadistic games. Unfortunately for them, AM has somehow obtained God-like technological power over physics, able to shape and project matter wherever it wishes, and also to keep the humans alive and immortal in their banged-up, miserable state. So, in effect, the protagonists spend an eternity in a kind of Holodeck-like hellscape, trying to figure out how to either escape or kill themselves.

Yeah, it’s heavy.

This enormous gulf between Asimov’s and Ellison’s visions of the future—an AI paradise versus an almost literal AI hell—is, in part, symptomatic of various generational and cultural shifts between the two men. I, Robot was published in 1950, on the tail-end of the Golden Age of Science Fiction, the time when the prosperity of America in the post-war years seemed destined to go on forever, fueled by newer and greater technological innovations (AI among them). In contrast, Ellison’s short story was published in 1967, at the height of a counter-cultural revolution that extended into science fiction literature —the New Wave that introduced some of my favorite sci-fi writers of all time, such as Samuel R. Delany, Ursula K. Le Guin, Roger Zelazny, and Ellison himself.

Thus, the difference between Asimov and Ellison’s work is essentially the difference between the lingering triumph of World War II and the horrors of VietNam. Between the optimism of the Atomic Age and the nihilism of the Cold War. In some ways, it’s also the difference between fantasy and realism, and between genre fiction and literary fiction. As dark as Ellison’s short story is, it’s also a much better work of fiction than Asimov’s. More convincing, too, alas. Told from the point-of-view of AM’s youngest victim, Ted, the story is filled with vivid, sharp writing and devastating passages, like this one:

Nimdok (which was the name the machine had forced him to use, because AM amused itself with strange sounds) was hallucinating that there were canned goods in the ice caverns. Gorrister and I were very dubious. “It’s another shuck,” I told them. “Like the goddam frozen elephant AM sold us. Benny almost went out of his mind over that one. We’ll hike all that way and it’ll be putrified or some damn thing. I say forget it. Stay here, it’ll have to come up with something pretty soon or we’ll die.”

Benny shrugged. Three days it had been since we’d last eaten. Worms. Thick, ropey.

You don’t have to be a literary critic to see that Asimov and Ellison are worlds apart, not just on the subject of Artificial Intelligence but on literally everything. Asimov was a scientist, a rationalist, and his optimistic views on the future of humanity were deeply rooted in the legacy of the Enlightenment. Ellison is more of a Gothic Romantic, full of existential angst and cosmic horror. His story is essentially an updated version of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, with the supercomputer in the role of the monster, determined to torment its creator.

Of course, the Frankenstein story is, itself, a reworking of an even older one—the Faustian myth. According to German legend, Faust is an intellectual who sells his soul to the devil in exchange for knowledge, and ends up going to hell. If the story seems familiar, it’s probably because the legend has been the psychological basis for countless tales of perverted science for centuries. Scientists, the story goes, want to attain the power of God, and thus end up being destroyed by their own hubris (often in the form of some infernal creation like Frankenstein’s monster or, more recently, SkyNet).

Perhaps the biggest irony here (at least for me, personally) is that while I have great admiration for Ellison’s story, and I believe it is a much greater artistic work that anything ever penned by Asimov, Asimov’s vision is probably more accurate of what we can actually expect from the AI revolution. For all the hype about AIs destroying art and music and literature and taking away our jobs, I think AI will be a net positive for humanity. Perhaps a big net positive. It’s already making contributions in the fields of materials science, medicine, and even fusion energy. Yeah, it’s probably going to take away some people’s jobs, but those were probably crap jobs anyway. (If you train an AI to do it as well as a human, it’s probably not worth doing.)

As for the whole AM/Skynet thing, I don’t worry about it because I don’t believe computers will ever become conscious. In fact, the very idea of a machine becoming conscious seems like a category error, the kind of conceit that will seem laughable a hundred years from now as those old drawings of “men of the future” with feathered wings strapped to their arms.

This doesn’t mean, of course, that we won’t, someday, create an artificial life form that might replace us. But it won’t be a computer. It will be…something else.

But that’s a subject for another post.