Of all the categories of genre fiction that I’ve consumed over my lifetime, fantasy has probably best the least represented. Sure, I love The Lord of the Rings, and The Narnia Chronicles, and the works of Ray Bradbury that I consider to be dark fantasy (see Something Wicked this Way Comes). But I don’t keep up with many modern fantasy writers nor read many contemporary fantasy novels.

So, you can imagine my surprise when I took a chance on Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi, a fantasy novel that made quite a splash when it came out in 2020, and I enjoyed the hell out of it. It’s a fascinating story of a man trapped in a labyrinth that he calls The House, and which is composed of endless Greco-Roman halls lined with innumerable statues and vestibules. There is a sky above and ocean tides below, which often flood the lower levels. The man is called Piranesi by the only other person (i.e., “the Other”) in The House, an older man who seems able to leave somehow, only to return with key supplies like vitamins and batteries, which he shares with Piranesi.

It’s a fascinating book, and unexpectedly suspenseful, too, especially when Piranesi begins having flashbacks of who he is and how he came to be in the House. This happens about the same time as the sudden appearance of mysterious, written messages that are scattered throughout the House. They seem to have been left by another, recent intruder (one who seems interested in helping Piranesi escape).

For me, at least half of the appeal of Piranesi lies in this whodunnit factor. Like the protagonist himself, I was caught up in the mystery of how he came to be there, who he is, and how he might get out. But the other half lay in the dizzying, intricate nature of the setting—the endless labyrinth that Piranesi inhabits. Such dreamlike settings are more common in literature than one might think, and their appeal is very much like that of a vivid, fabulously detailed diorama, of the sort that all children love to gaze into (and imagine themselves inside).

I don’t know what it is, exactly, about mazes, labyrinths, and castles that evokes the power of imagination, But I think it has to do with their endless novelty, the promise of infinite rooms and corridors that we, like children, would love to explore. More to the point, such structures also symbolize the power of imagination—especially the child-like imagination that each of us still harbors. That’s why there is such a grand tradition of castles and mazes in fantasy literature and mythology, from the Minotaur’s labyrinth to the vast, rambling ruins of the Gormenghast trilogy.

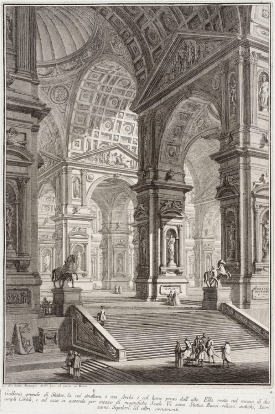

Clarke herself acknowledges this tradition in her main character, Piranesi, who is named after Giovanni Battista Piranesi, the 18th Century illustrator who was famous for his drawings of impossibly grand and complicated imaginary buildings. His most famous works are a series of etchings titled Carceri d’invenzione (Imaginary Prisons), and these are, themselves, part of a much older tradition of so-called capricci, drawings that depict architectural fantasy.

Continue reading “The Enchanting Labyrinths of Vortex Fiction”