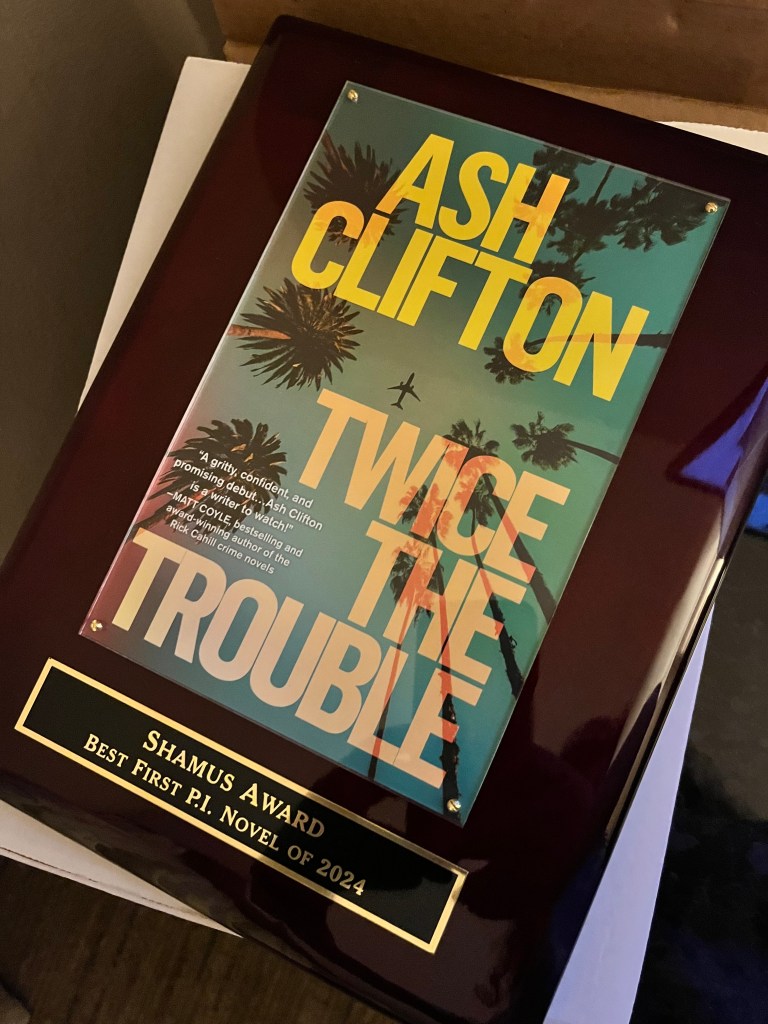

I’m very honored to announce that Twice the Trouble has won this year’s Shamus Award in the First Novel category. Many, many thanks to the Private Eye Writers of America, my incredible agent Cindy Bullard, and Crooked Lane Books!!!

I’m very honored to announce that Twice the Trouble has won this year’s Shamus Award in the First Novel category. Many, many thanks to the Private Eye Writers of America, my incredible agent Cindy Bullard, and Crooked Lane Books!!!

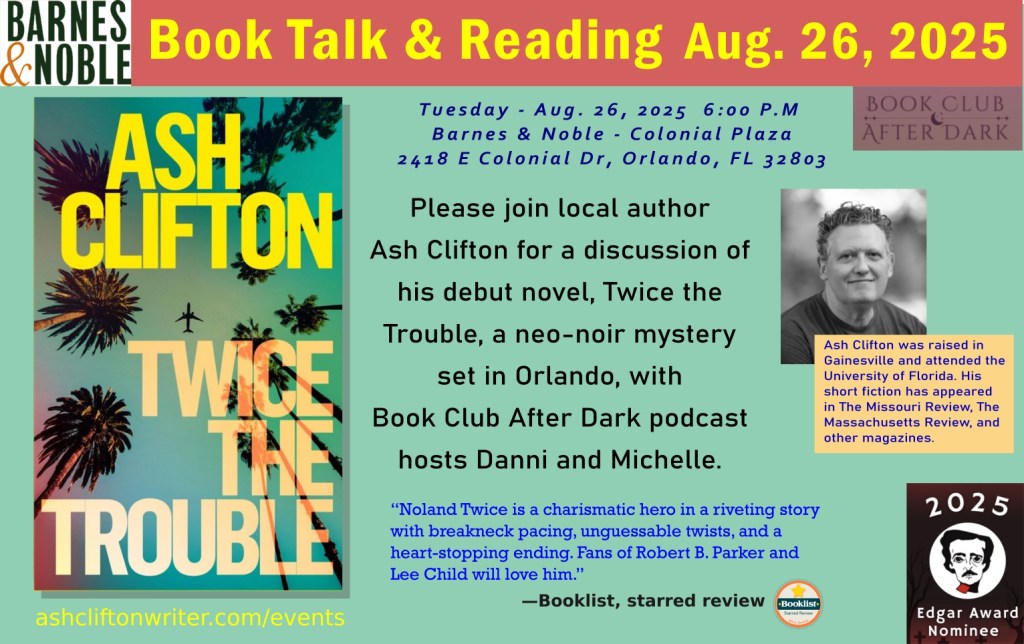

Well, Cathy and I got back from Orlando on Thursday, and this is the first chance I’ve had to write a post about it. All in all, it was a fine trip! My book talk at Barnes and Noble went well, mostly due to Danni and Michelle, the hosts of the excellent podcast Book Club After Dark, who were nice enough to interview me. They asked great, insightful questions, and I had a lot of fun. The turn-out was modest, but the people who did show up seemed really interested. They asked some great questions, too. It was especially nice to see my old friend Norm, who came to the event to cheer me on. He also snapped the picture above.

Afterward, Cathy and I had a great dinner and some fine beers at the Harp and Celt Pub downtown. The next day, we did a driving tour of Orlando, Noland Twice’s home turf, refamiliarizing ourselves with our old stomping grounds. As one might expect, parts of the city seem completely different from when we lived there, while other parts seemed exactly the same. Overall, O-Town still feels like two cities. There’s the lovely, old, Southern city, with its tree-shaded streets and gorgeous houses from the 1930s and ‘40s. Then, there’s the litter-on-a-stick, urban sprawl of Generica, with its strip-malls and fast-food shacks and liquor stores. And traffic. Lots of traffic. The really sad part about Orlando is that you have to drive through the nasty bits to get to the nice, old, quaint bits. But oh well. I still love the city.

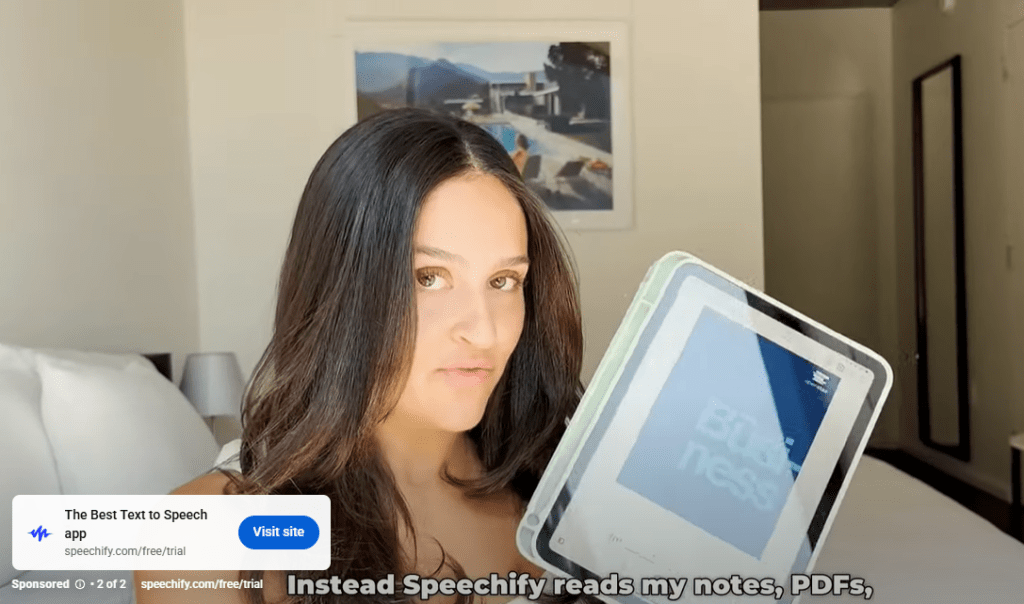

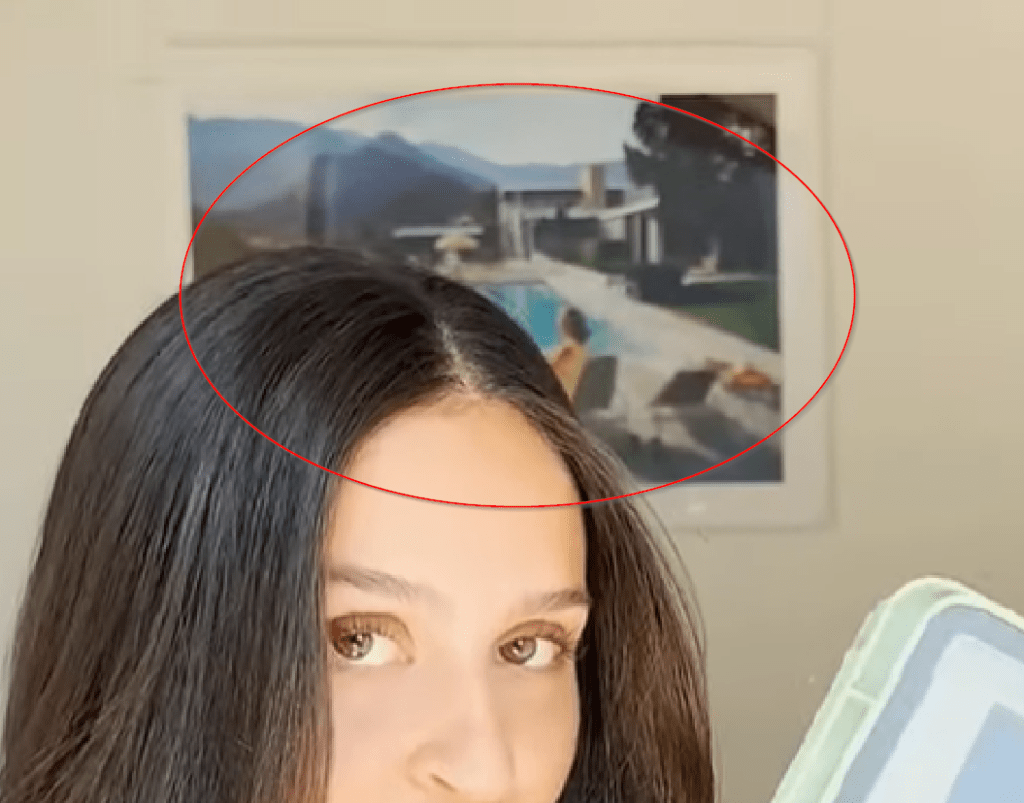

When we were done exploring, Cathy and I drove down Mills Avenue and visited the Mennello Museum of American Art, which is perhaps the best small museum I’ve ever visited. I was especially taken with their current exhibit, entitled Pool Party, which had lots of amazing photos and paintings of American pool culture from all over the country. I was especially taken with this 1970 photo, above, by former combat photographer Slim Aarons. It’s titled Catchup by the Pool, and it seems to encapsulate the entire upper-class, White, suburban culture of the U.S., right on the cusp between two equally garish decades. And yet, it’s also kind of…sweet. I find myself wanting to go to this party.

And then, just this morning, in one of those instances of synchronicity that seem to happen fairly often to me (and which I blog about, a lot), I happened to be presented with a YouTube ad (for Speechify, of all things). Before the skip button came up, I had to leave the room, so I paused the ad so I wouldn’t miss the beginning of the actual video I was waiting for. (Just to prove I wasn’t crazy, I did a screen grab, above left.)

When I came back, I noticed that there was something weirdly familiar about the freeze-frame that I happened to pause on. If you look at the background, on the wall of whatever apartment or motel room the ad was apparently filmed in, you can see—lo-and-behold!—the same photo by Slim Aarons.

What are the odds? Like, a bazillion-to-0ne! Talk about synchronicity-on-steroids!

Anyway, it seemed like a magical end to a good trip.

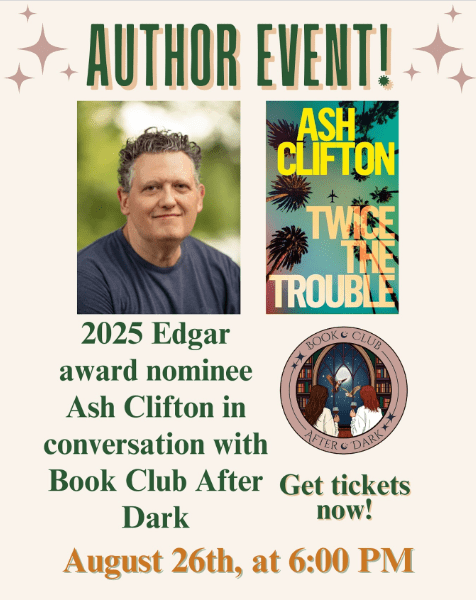

I’m heading off to O-Town tomorrow (yes, the setting for Twice the Trouble) to hold an author talk at the Barnes & Noble on Colonial. If you’re in the area, please come! Danni and Michelle, the hosts of the excellent Book Club After Dark podcast will be presiding.

(This is a ticketed event, so please click here to get your ticket.)

As I’ve stated before, one mark of a truly fine mystery novel—for me at least—is if I feel the need to go back and reread it. This isn’t just a matter of me waiting long enough to forget whodunnit (a period of time that grows shorter the older I get), it’s also an indication that something about the novel stuck with me, and made me want to revisit its imagined world.

So, it’s perhaps not surprising that I find myself rereading many of Edith Pargeter’s (writing as Ellis Peters) Brother Cadfael novels. Currently, I’m on The Rose Rent, which is about as fine an episode in the series as any. It has all the components of a truly great mystery novel—namely, a compelling and complicated sleuth; an entrancing and alien setting; original and interesting secondary characters; and a multi-layered plot.

And a voice. Of course, a great narrative voice. Take the opening paragraph of the novel:

By reason of the prolonged cold, which lingered far into April, and had scarcely mellowed when the month of May began, everything came laggard and reluctant that spring of 1142. The birds kept close about the roofs, finding warmer places to roost. The bees slept late, depleted their stores, and had to be fed, but neither was there any early burst of blossom for them to make fruitful. In the gardens there was no point in planting seed that would rot or be eaten in soil too chilly to engender life.

I love the elegance and almost romantic feel to this passage, which is characteristic of all Pargeter’s writing. You feel like you’re in competent hands, which is crucial considering that you’ve been transported to England in the Twelfth Century. (Specifically, to Shrewsbury, the town where Cadfael lives as the resident herbalist of the local Benedictine monastery.) I love the sense of desolation in this opening. We can almost feel the lingering winter, which has gone on too long and threatens the well-being of the town, including the ordinary folk, the monks, and even the nobles. It also suggests the coming tragedy of the murder around which the story will be revolve—that of a young, love-stricken monk who is killed trying to protect the woman with whom he has become infatuated.

Yes, it’s a desolate opening. But with Pargeter, you never really feel hopeless. Sure, it’s the Dark Ages, but her stories are populated with good, strong, shrewd people who always find a way to make the best of things. Take this paragraph, which comes a bit later and introduces Brother Cadfael himself:

Brother Cadfael, preoccupied with his own narrower concerns, continued to survey the vegetable patch outside the wall of his herb-garden, digging an experimental toe into soil grown darker and kinder after a mild morning shower. “By rights,” he said thoughtfully, “carrots should have been in more than a month ago, and the first radishes will be fibrous and shrunken as old leather, but we might get something with more juices in it from now on. Lucky the fruit-blossom held back until the bees began to wake up, but even so it will be a thin crop this year. Everything’s four weeks behind, but the seasons have a way of catching up, somehow. Wareham, you were saying? What of Wareham?”

#

He is speaking, of course, to his best friend, Hugh Berenger, the Sheriff of Shrewsbury. Berenger is a much younger man, but like Cadfael he is world-weary, experienced, and tough. Indeed, many of the best novels in the series depict bad guys who underestimate Berenger, with his mild demeanor and slight build, as weak. He is, in fact, an intelligent man and a cunning fighter. Berenger has just brought news of the most recent battle of the on-going English civil war (the Anarchy) which serves as the backdrop for all the novels. Berenger, we know, has befriended Cadfael in part because they have both been soldiers—in Cadfael’s case, a veteran of the First Crusade, which caused him to live in the Middle East for many years, where he lived with a Muslim widow and fathered a child with her.

A great part of the appeal of these novels is this tension between two sides of Cadfael’s character. He is the very opposite of an oblate—a person who has come into the monastery as a child. Rather, Cadfael has converted later in life, after have seen many terrible and wondrous things and had many worldly experiences. As such, he brings a shrewd, wise perspective to his role as a monk, healer, and protector of the innocent—a shrewdness that is matched by the “hatchet-faced” Abbot Rudolfus, who often conspires with Cadfael to bend the rules in favor of a remorseful miscreant or helpless person.

And, of course, there is just Pargeter’s unerring talent for winning, memorable description. For instance, take this passage, in which a self-serving (and possibly villainous) young character, Vivian, is introduced.

[Vivian] was a very personable young man indeed, tall and athletic, with corn-yellow hair that curled becomingly, and dancing pebble-brown eyes in which a full light found surprising golden glints. He was invariably elegant in his gear and wear, and knew very well how pleasant a picture he made in most women’s eyes. And if he had made no headway yet with the Widow Perle, neither had anyone else, and there was still hope.

The woman on whom Vivian has set his sights is Judith Perle, a young widow who has leased her old house to the monastery for the meager “rent” of a single rose per year, plucked from the bush that grows outside the doorway. Judith is, of course, very rich woman, and must of the plot revolves around a murder who is intent of separating her from that wealth—even if this means killing her in the process.

The Rose Rent is a great mystery novel. Check it out…

If you’re going to be in Central Florida later this month, please try to attend my book talk on August 26 at the Barnes & Noble with Danni and Michelle, the hosts of the Book Club After Dark. We will be discussing Twice the Trouble, the paperback edition of which goes on sale that day.

The event is ticketed, so please click here to get your (free) ticket and reserve a seat.

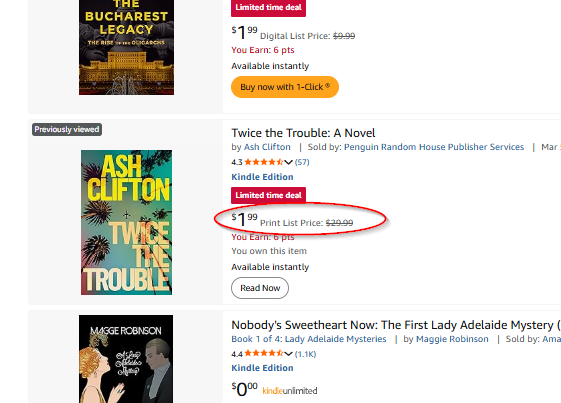

What can two bucks buy you in today’s economy? A copy of my book, that’s what! For the entire month of August, the Kindle edition of Twice the Trouble is on sale for just two bucks. That’s right. Just two Ameros!

You should buy it! Right now! Don’t give me that “I don’t even have a Kindle” crap! Just buy the damned book. Buy buy buy!

What’s worse than a shameless plug? A rerun of a shameless plug!

I’ve been laid up with back problems all week and haven’t been doing much, so I thought I would repost this oldie. I had a lot of fun writing this essay. Many thanks to the good people at CrimeReads for giving me the opportunity.

Check it out…

In this latest episode of our on-going YouTube series, Read a Classic Novel…Together!, Margaret and I go over the first half of The Dispossessed, Ursula K. Le Guin’s classic literary science fiction novel. We also address other topics such as was Communism doomed from the start, are flashbacks overused in fiction, and do New York City rats constitute their own, separate species?

Check it out!

I’ve read a lot of biographies in my time. Some of my favorites have been about great monarchs (Catherine the Great by Robert Massie), presidents (Truman by David McCoullough), scientists (Oppenheimer by Kai Bird), architects (Frank Lloyd Wright by Meryl Secrest). Now, I can finally add religious leaders to my list. Or at least one religious leader, the Rebbe Menachem Mendel Schneerson.

It’s taken me this long, I think, because while I am fascinated by the study of various religions, I am not very interested in the life-story of most religious leaders. This is, in part, a consequence of the vexed historicity of such figures. Usually, they lived in the distant past, shrouded in veils of myth, with the actual, living person being lost to time. But this is not the case with Rebbe Schneerson. After all, he was not only a very recent figure, having passed away in 1994, but he spent most of his life right here in the United States—Brooklyn, in fact, that modern locus of Hasidic Judaism, and especially the Chabad-Lubavitch dynasty, which Schneerson led since 1951, succeeding his father-in-law.

As Joseph Telushkin recounts in his excellent book, Rebbe: The Life and Teachings of Menachem M. Schneerson, the Most Influential Rabbi in Modern History, Schneerson was essentially appointed to the position by general acclimation, bypassing the previous Rebbe’s son who had been the heir apparent. Community leaders and other rabbis in the movement were simply awed by Schneerson’s considerable intellect—he spoke half-a-dozen languages, had an Engineering degree, and was considered a “genius” in Talmudic study from the age of seventeen—and pressured him to take the job.

Which, thankfully, he did. I never thought I would ever read a book about an orthodox Jewish rabbi and, at the end, think to myself: “Wow, he seems like a really cool guy.” After all, I’m used to being utterly repulsed by most “leaders” in my own religious sphere, Christianity, with the exception of the current Pope and his immediate predecessor. But the more I read about Schneerson, the more impressed I was, not only by his general wisdom in matters of religion and morality, but also in his endless, practical concern for the well-being of ordinary (often poor) people, both Jews and Gentiles.

One example Telushkin provides involves Shirley Chisholm, the first black woman elected to Congress. Racist creeps in the House refused to appoint her to any high-level committees and instead stuck her on the Agriculture Committee, which, considering Chisholm represented a section of New York, seemed absurd to most observers. Yet, the snub also presented an opportunity that she, herself, never suspected. As Telushkin writes:

She soon received a phone call from the office of one of her constituents. “The Lubavitcher Rebbe would like to meet with you.” Representative Chisholm came to 770. The Rebbe said, “I know you’re very upset.” Chisholm acknowledged both being upset and feeling insulted. “What should I do?” The Rebbe said: “What a blessing God has given you. This country has so much surplus food and there are so many hungry people and you can use this gift that God’s given you to feed hungry people. Find a creative way to do it.”

And she did, creating one of the first federal food-aid programs in the history of the United States, in which surplus food was bought by the government from American farmers and distributed to poor people, thus helping the recipients, the farmers, and pretty much everyone else.

On a more personal level, Schneerson always emphasized the importance of kindness and compassion over religious stricture. In one of his drashas (sermons), he famously told the story of how his predecessor, the Alter-Rebbe, once stopped in the middle of his Sabbath observations to attend to a young woman who had just given birth and who had been left alone by her family so that they could attend synagogue. Telushkin writes:

That day, the Alter Rebbe, having somehow learned that the new mother was alone, was suddenly overwhelmed with the certainty that the woman required someone to attend to her needs immediately; it might well be a matter of life and death. And since no one else was taking care of her, he concluded that he should be the one to do so.

This story apparently shocked his followers in way that most modern, secular people like myself cannot really appreciate. The idea that a rabbi might 1.) forsake the Sabbath observations in order to 2.) do menial work on the Sabbath like chopping wood and 3.) do so for an ordinary woman was radical in the extreme.

Such was Schneerson’s boundless respect and love for ordinary people that he was always concerned about inadvertently embarrassing or insulting anyone, especially those who were most vulnerable. Decades before the so-called woke movement (a bad name for a very noble cause), Schneerson refused to use the word “handicapped” in reference to battle-maimed Israeli soldiers. Telushkin writes:

Referring to the fact that such people are designated in Israel as nechei Tzahal, “handicapped of the Israel Defense Forces,” the Rebbe addressed the men as follows: “If a person has been deprived of a limb or a faculty, this itself indicates that G-d has also given him special powers to overcome the limitations this entails, and to surpass [in other areas] the achievements of ordinary people. You are not disabled or handicapped, but special and unique as you possess potentials that the rest of us do not. I therefore suggest”—the Rebbe then interspersed with a smile—“of course it is none of my business, but Jews are famous for voicing opinions on matters that do not concern them—that you should no longer be referred to as ‘disabled veterans’ but as ‘exceptional veterans’ [metzuyanim], which more aptly describes what is unique about you.

In addition to being a genuinely good and wise person, Schneerson also seemed to have what can only be described as superpowers. He worked eighteen hours a day, six-days-a-week, for most of his life. Being busy with his primary duties during the day, he met with people seeking advice in the evenings, often as late one or two o’clock in the morning. Some of the people seeking advice including future and former Prime Ministers of Isreal such as Menachem Begin, as well as many other powerful and influential figures. But, more of than not, they were comprised of ordinary men and women in his congregation. I was especially impressed with Telushkin’s story of a young woman, Chana Scharfstein, who often came to his office seeking academic as well as personal (dating) advice:

The Rebbe clearly knew his agenda for this meeting, and the conversation quickly turned in a personal direction. At a certain point, he asked Sharfstein if she felt ready to get married. Sharfstein told him that she had begun dating—in Chasidic circles, young men and women date only for the purpose of marriage—and the Rebbe asked her about a specific young man. She recalls being taken aback and thinking to herself, That’s interesting that he should ask about somebody that I had met. Sharfstein told the Rebbe that she had met the young man he mentioned, that he was clearly a fine person, but not for her. The Rebbe said all right, and then mentioned another name, and again it was someone to whom Sharfstein had been introduced. Here, too, the young man was very nice but not for her. Then the Rebbe mentioned a third name, and a fourth, “and I became really uncomfortable then. How did the Rebbe choose all the names of young men (bachurim) that I had met? I was just absolutely overwhelmed that he should mention people that I had actually met.” Only later did she learn that prior to going out with a girl, each bachur in Chabad would write to the Rebbe to inquire if the girl seemed suitable for him, and so the Rebbe, who obviously had responded in each case that Chana Zuber was suitable, had a very precise idea of all the people with whom she had gone out. But even taking all this into account, Sharfstein still remained staggered at the Rebbe’s recall. After all, he “was [already] a world leader at this time, and to keep track of each person and who had been dating whom, it’s really mind-boggling.”

As this story relates, Schneerson’s remarkable memory and formidable intelligence were often sources of awe among those in congregation. Another example involves a young student, Irving Block, who came to discuss philosophy with the Rebbe:

At the time, Block, who was studying for an MA in philosophy, was immersed in the study of the great Greek thinkers, Plato in particular. And that’s the direction in which the Rebbe led the discussion. Only Block didn’t realize at first to whom the Rebbe was referring, because it was a man named Platon about whom the Rebbe started talking. It finally struck him that Platon is how the name of the Greek philosopher is written in Greek, though in English his name is always pronounced as Plato. It’s not that the n is silent in English; it isn’t written at all. This was Block’s first surprise of the day. The man seated in front of him, dressed in the garb of a Rebbe, obviously knew about Plato, or Platon, from the original Greek and pronounced his name as it was supposed to be pronounced.

Block was not only amazed by the Rebbe’s deep understanding of the “Platon’s” philosophy but by his utter rejection of it. (Plato believed that the nuclear family was an evil institution and should be abolished, an idea that was in direct contradiction to all humanist values, including those of Judaism.)

In recounting such stories as these, Telushkin’s book is really more of an appreciation or tribute than an in-depth biography. And yet he manages to relate the primary facts of Schneerson’s remarkable life with grace. Born in Imperial Russia, Schneerson moved with his family to the US in the spring of 1941. Thereafter, he served as Rebbe for over 50 years, finally passing away in a time when the world was much changed.

One might say that he was born in the time of Tsars and passed away in the time of the internet. And, in all that time, one thing remained constant: his steadfast commitment to the practical well-being of all the people, rich and poor, high and low, in his community and around the world. Truly a person worth reading about. Check it out…

I am very happy to announce that I am a finalist in the Best First P.I. Novel category for this year’s Shamus Awards! Many, many thanks to the good people of The Private Eye Writers of America for this great honor.

Good luck to all the other nominees, especially my friends Alexis Stefanovich-Thomson and Henry Wise. I hope one of us wins. And I really hope it’s me.