As usual, it took us a while, but Margaret and I finally posted our second (and final) book talk episode on Ursula K. Le Guin’s classic sci-fi novel The Dispossessed. I will probably be doing another post on my final thoughts about the book soon. In the meantime, please check out the videos (Part I is here) and give them a like.

Category: Sci-Fi

Classic Sci-Fi Book Cover: “The Deathworld Trilogy”

Harry Harrison’s Deathworld trilogy kept me sane during one long-ago summer when I was bored and lonely. As I recall, my father gave it to me, having bought it in an airport bookshop after a long trip. (Yes, he was a good dad.)

Harrison is most famous for his Stainless Steel Rat series, but I liked these books better. As in all of Harrison’s work, the Deathworld stories center around a trickster anti-hero—in this case, Jason dinAlt, a smart, conniving rogue who is also telepathic. (He uses his E.S.P. to cheat at cards and thus travels from casino-to-casino, and planet-to-planet, having adventures but never a real job.)

Looking back on it, I would bet that this cover by illustrator David Egge, depicting dinAlt in futuristic battle gear, had a lot to do with further popularizing the military science fiction sub-genre, of which Robert Heinlein’s Starship Troopers is the best-known example. (Current examples are too numerous to name.) In fact, the Deathworld books are not military sci-fi. The characters dress like soldiers because they live on a very dangerous planet named Pyrrus (as in pyrrhic; get it?) where every living thing from plants to animals is lethal to humans. Indeed, the entire ecosystem of Pyrrus seems determined to kill all the human colonists, for reasons that dinAlt will try to discover using his telepathic powers as well as his finely honed survival skills.

The Deathworld books are just fun, well-plotted, fast-paced adventure stories, reminiscent of science fiction’s Golden Age—albeit with a bit more wit attached to them than the average sci-fi fair. Moreover, Harrison should be lauded for the series’ strong ecological message (well hidden, at first, but definitely in there), which was usual at the time, especially in “guy’s” books.

Check them out…

What I’m Reading: “The Future Was Now”

In the summer of 1982, I was a very unhappy boy. Being a nerd in an upper-class high school full of preppies and jocks, I didn’t fit in very well. I hated most of my classes. I had a few good, close friends (including some jocks), but that was it. As one would expect, I spent a lot of time in my room reading sci-fi novels and typing short stories on the typewriter my mother had bought me.

The only thing that kept me sane was movies. Fortunately, 1982 turned out to be the most incredible time in cinematic history to be a nerd. A string of classics came out that summer including Blade Runner, The Thing, The Road Warrior (a.k.a. Max Max II), Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, Poltergeist, Tron, Conan the Barbarian, and (the 800-pound gorilla) E.T. Even at the time, I was cognizant that this bumper crop of cool films, all coming out within a few weeks of each other, was a very unusual, almost magical development. I spent many hours on the bus with my friends going to and from the local cineplex, where we watched many of these films over and over.

For forty years, I labored under the delusion that this rapid series of classics was just a lucky coincidence. But while reading Chris Nashawaty’s fine nonfiction book, The Future Was Now: Madmen, Mavericks, and the Epic Sci-Fi Summer of 1982, I learned otherwise. A good historian will reveal that any event, no matter how seemingly incredible or unlikely, actually emerges logically from previous events. That is, the seeds were planted years or even decades before. And in 1982, main seed was a little film called Star Wars. As Nashawaty explains:

Continue reading “What I’m Reading: “The Future Was Now””There’s an unwritten rule for reporters and trendwatchers who cover Hollywood that if you want to know why a movie—or a particular group of movies—was made, all you need to do is look back and see what was a hit at the box office five years earlier since that’s the typical gestation period for studio executives to spot a trend, develop and green-light an imitator, push it into production, and usher it into theaters. And the summer of 1982 would prove no exception, coming exactly five years after Star Wars. What seemed underreported, however, was how this new wave of sci-fi titles had been conceived and carried out. It is a wave that we’re still feeling the aftereffects of, for better and worse, today.

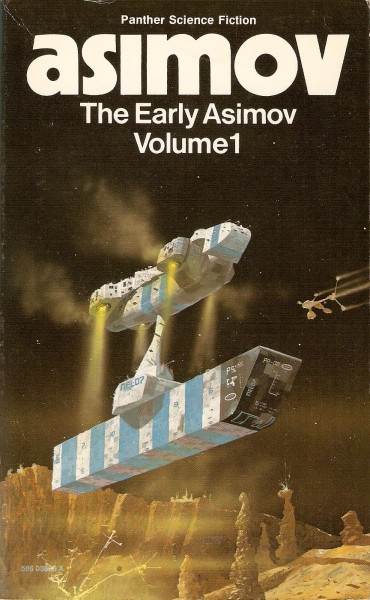

Classic Sci-Fi Book Cover: “The Early Asimov – Volume 1”

Ever since I started this series, I’ve been meaning to write a post about Chris Foss. For a sci-fi nerd growing up in the 1970s and ’80s, it was impossible not to see and be familiar with Foss’s artwork. After all, he illustrated more than 1,000 book covers during his long and celebrated career. His style is so distinct and memorable that one can recognize it on a bookshelf (or a computer screen) from twenty yards away.

I remember seeing some of his sci-fi book covers back in the 1970s and being struck by their originality and vividness. He specialized in images depicting spaceships or futuristic craft, which he rendered with a strange, industrial-style realism that was new and striking. In particular, his spaceships look like real, constructed things with visible welds and spanners and plates, often painted in bright, almost nautical color schemes. He also likes to depict smoke. Or mist. Or dust. Something to give the otherwise static vacuum of space some drama and sense of motion.

His work was so good, in fact, that no one seemed to care whether the depicted image had anything to do with the plot of the book itself. Often, it did not. But that didn’t matter. The cover always said two things: science fiction and drama. And that was enough. It was plenty.

While I was doing a bit of research for this post, I was delighted to learn that Mr. Foss is still alive and still working. You can see more of his artwork on his website, which I encourage everyone to visit.

Book Talk – “The Dispossessed”, Part 1!

In this latest episode of our on-going YouTube series, Read a Classic Novel…Together!, Margaret and I go over the first half of The Dispossessed, Ursula K. Le Guin’s classic literary science fiction novel. We also address other topics such as was Communism doomed from the start, are flashbacks overused in fiction, and do New York City rats constitute their own, separate species?

Check it out!

Science Fiction’s Latest Utopian Dream

When I was a kid, my parents bought me a book called A Pictorial History of Science Fiction by David Kyle, which covers the history of science fiction illustration from Jules Verne all the way through the 1970s. (The book was printed in 1976.) I still have it. I remember being especially enthralled by covers from pulp magazines in the 1930s like Astounding Science Fiction and Amazing Stories. Many of these covers were devoted to some artist’s vision of The City of The Future—usually some towering, high-tech, hive-like metropolis.

It makes sense that sci-fi nerds of the 1930s would imagine a vertical, urban future. At the time, the most sophisticated places on earth were the great western cities of Europe and America. Paris. Berlin. And especially New York—Manhattan—with its great skyscrapers reaching ever higher. The obvious extrapolation of this trend was that someday everyone would be living in some vast, super-tall version of New York or Los Angeles, with buildings hundreds of stories high and millions of people living in close proximity. Ramps and walkways would connect these towers in the sky, allowing residents to hardly ever venture down to street-level. Airplanes, blimps, and elevated high-speed trains would speed residents from one end of the city to the next.

For most of these sci-fi artists and writers, this was going to be a good thing. A utopian vision, in fact. Future cities would be paradises of high technology, dense but egalitarian. Robots would do all the dirty work, and everyone would be rich. For others, though, the City of the Future would be a capitalist hell, with the decadent rich living high above the exploited poor. These upper-classes would hoard resources and technology, either out of fear or greed or sheer meanness. It is this dystopian vision that informs works like Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, as well as every instance of the cyberpunk genre from William Gibson’s Virtual Light to Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner.

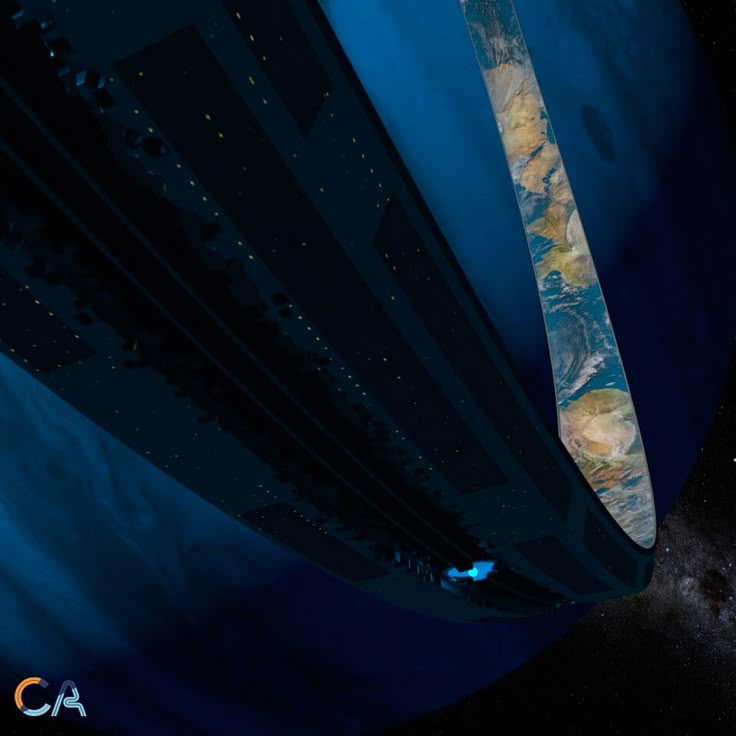

Despite this dark side, however, the vision of an artificial, high-tech utopia has long existed in sci-fi, and it still does today. But the vision itself has changed. Relocated. These days, the City of Future is almost invariably depicted as being in outer space—”off-world,” in the lingo of movies like Blade Runner—either on a nearby planet or the moon or on a station floating in space.

Space stations, in particular, have captured the imagination of science fiction fans for the past four decades, ever since Princeton physicist Gerard K. O’Neill published The High Frontier: Human Colonies in Outer Space. In that landmark book, O’Neill explained the advantages of living on a space colony as opposed to a land-based colony like Mars or the moon. These include the fact that one could spin the colony to produce the same gravitational pull as Earth, thus avoiding any physiological problems the colonies might suffer from living on a smaller world. Unlimited solar power is another plus, as is the fact that, living outside the gravity well of a planet or moon, travel between colonies would be vastly cheaper. Trade would thrive, fueled by a steady flow of cheap, raw materials from the asteroid belt and various moons throughout the solar system.

O’Neill was the first, legit scientist to take the idea of people living in outer space seriously, and he was able to back up his ideas with hard data, including actual blueprints for working stations. Namely, he invented the O’Neill Cylinder, a tube-shaped world the size of a city with its residents living on the inner surface. Other designs were created by a diverse group of like-minded theorists. Of these, the most compelling is the Stanford torus (named for the university where the plan was cooked up). Instead of a tube, it’s a giant wheel. For whatever reason, it’s this ring-like design that has dominated most sci-fi stories of recent decades. Larry Niven’s Ringworld is basically a humongous Stanford torus (large enough to encircle a star). And the design is also represented in the wheel-worlds of the Halo videogame franchise and the fabulous Orbitals of Iain Banks’s The Culture novels.

As was the case with the high-rise super-cities that were imagined of the 1920s, the space-colony vision isn’t always utopian. In the 2013 film Elysium, for example, the titular space station is an exclusive haven for the ultra-rich, desperate to escape an Earth ravaged by global warming and end-stage capitalism. Perhaps this is why many people become uneasy when billionaire tech-bros like Jeff Bezos openly embrace the idea of building giant colonies in space. They seem to be confirming the dystopian side of the space colony coin.

I have very little in common with Jeff Bezos. But, like him, I must confess to be completely captivated by the idea of colonies in space. They are not only fun to imagine, but I believe that they probably do represent the best possible, long-term vision for the future of humanity. I don’t know if they will happen, but I hope they do.

Why do I harbor this hope? Lots of reasons. For one, space colonies offer our best chance of surviving as a species into the far future. Even if we somehow avoid the worst consequences of global-warming, there will always be some other looming disaster that threatens to exterminate life on Earth, from planet-killer asteroids to super-volcanoes to the next pandemic. With space colonies, there would soon be more people living in space than earth—perhaps trillions of people within a few centuries—thus making us a lot harder to wipe out.

For another, the quality of life on space colonies would probably be much, much higher for the average citizen than it is likely to ever be on Earth. This is due to the advantages I listed above, like abundant solar power and cheap resources for asteroids. And overpopulation would never be a problem—at least, not for long. Whenever a colony got too crowded, any citizens who craved more elbow-room would simply build a new space colony and move into it.

Of course, many people will never be disavowed of the idea that space colonies represent nothing more than a “Plan-B” for the ultra-rich. That is, after all the rich people trash the earth with their greed and unfettered capitalism, space colonies give them the ultimate chance for escape from the consequences of their actions.

This is, I think, a real possibility for why space colonies might eventually be built. But it’s not the only possibility, nor even the most likely. Rather, my guess is that space colonies will be built for the positive reasons that I mentioned—abundance, room, and quality of life. Indeed, one could imagine an era—in the three or four-hundred perhaps—when so many people choose to emigrate to space that Earth could become a giant Hawaii. That is, an ecological and historical preserve, with less than a billion people on the entire planet. People who are born on space colonies might endeavor to make a pilgrimage down to Earth at least once in their lives, the way many Irish-Americans eventually take a vacation in “the Old Country” of Ireland.

One thing Bezos and I vehemently disagree on (one of many things, actually) is the time-table for when space colonies will eventually be built. It won’t happen any time soon–not in Bezo’s lifetime (unless he has a store of some immortality drug stashed somewhere), nor in mine, nor in the next generation. But I think it will happen.

Which leads to the question: Will space colonies really be utopias? That depends on your definition of utopia. If a citizen of mediaeval Europe were to be magically transported to a modern, western city, they would probably perceive it as a utopia. I mean, running water? Toilets? Central heating? All the food you can eat? How much more utopian can you get? Such a person would probably dismiss any argument we might make to the contrary—that people in the 21st Century have as many problems as those in the 13th. Bullshit, they would probably say. And they’d be right. For, while modern western civilization isn’t perfect (and it seems to be getting less perfect by the day, alas), it’s still pretty freakin cool. Yes, we still have evil and stupidity and greed. And all of those human failings will find their way onto space stations.

But still, we will be making progress. It’s a worthwhile vision, and exactly the kind of dream that good sci-fi can deliver.

And should. At least some of the time.

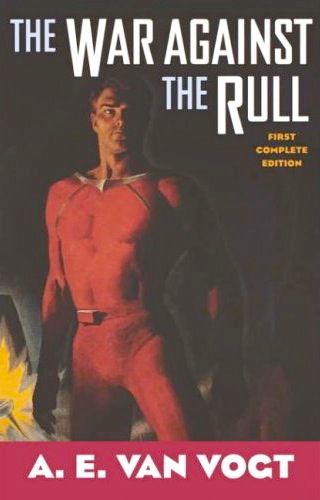

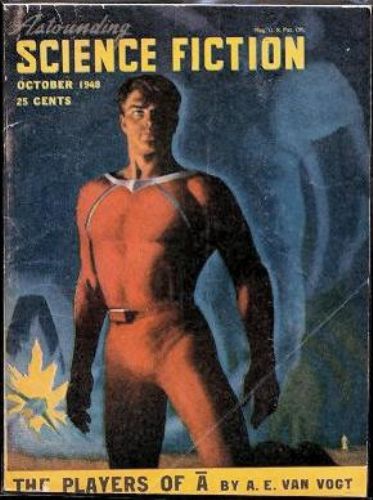

Classic Sci-Fi Book Cover: “The War Against the Rull”

This entry in my on-going Classic Sci-Fi Book Covers series is both old and new. That is, it’s a modern touch-up of the cover from the October 1949 edition of Astounding Science Fiction painted by Hubert Rogers. That issue included a work by A.E. van Vogt, but not the one we are interested in here. This modern version is from a 1999 edition of van Vogt’s classic sci-fi novel, The War Against the Rull, which I distinctly remember devouring in two days when I was in eighth-grade.

I like this cover a lot. It’s not just a classic. It’s an archetype. Specifically, the archetype of the heroic (America) scientist, a buff intellectual and polymath whose ilk could be found in countless works of Isaac Asimov, Robert Heinlein, Roger Zelazny, and on an on. In The War Against the Rull, the man is Dr. Trevor Jamieson, a brilliant scientist who is also a fierce warrior and survival-expert. He’s stranded on an alien planet with a huge, six-legged, intelligent creature called an ezwal who wants to kill him. But when both Jamieson and the ezwal encounter a mutual enemy—a race of aggressive, centipede-like aliens called the Rull—they decide to work together to survive.

It’s a great story, like so many from the sci-fi’s Golden Age. I’ve written before about why sci-fi novels from that era are so much more enjoyable (to me, at least) than most of those written in the last ten years or so. I think it has to do with the gritty humanity of such stories. Yeah, Jamieson is essentially a comic-book character (think Doctor Quest and Race Bannon rolled into one), but van Vogt does a great job of making you believe he’s in real trouble. The ezwal, too—he’s a compelling character in his own right. You get involved in the desperate nature of their situation, and you keep reading to see how they will get out of it.

Anyway, check it out if you can…

Classic Sci-Fi Book Cover: “This Immortal”

My privious entry in this continuing “Classic Sci-Fi Book Covers” series was also devoted to Roger Zelazny, so please forgive me for double-dipping into the Zelazny well. But I couldn’t resist talking about one of Zelazny’s other great novels, …And Call Me Conrad—published in 1966 as This Immortal. Most people have never heard of it, but it’s an interesting book for several reasons.

For one, it was Zelazny’s first novel, and it has many of his signature obsessions (e.g, ancient mythology mixed with science fiction; a wise-cracking anti-hero who is also an Übermensch; epic fight scenes; etc.). For another, it actually won a Hugo Award, tying in 1966 with a slightly better-known book…Frank Herbert’s Dune. And finally, it’s just a hell of an entertaining adventure tale.

I chose this cover (by fantasy artist Rowena Morrill) because it really captures the sense of the book’s main character, Conrad Nomikos, a world-weary man-of-mystery who might be immortal. (The text suggests that he is at least a century old, and hints that he might be several thousand years older still.) He works as director of a government agency tasked with protecting and preserving the surviving relics of a destroyed earth. A nuclear war referred to by the characters as “The Three Days” has occurred many decades before, leaving most of the planet uninhabitable. The survivors, which include a wide variety of mutants both human and animal, live mainly on islands like Greece, Conrad’s home.

And that’s not even the main subject this wild, wild little book. Conrad is assigned the duty of escorting a group of VIP tourists—including Cort Myshtigo, an alien from the Vega star system whose race has purchased earth as a kind of vast museum—as they tour the planets once great sites (now ruins). Conrad soon realizes that another of the tourists, an Egyptian assassin named Hassan with whom Conrad has befriended in the past, is secretly on a mission to kill the Vegan. Hassan, it seems, has been hired for this task by an obscure, underground political group who want to reclaim earth for humanity. So, Conrad finds himself not only being a tour-guide but also an unpaid protector of Myshtigo—who he hates.

It’s a crazy book, and the cover conveys this craziness well. Though the edition is from 1980, the cover really feels like a 1970s cover, with its vaguely photorealistic painting of a ruggedly handsome dude with great hair (think Roger Staubach in his prime). I also like how Morrill works in the other tropes of the book—its setting among Greek ruins, as well as the presence of some mythological creatures in the background (which, the reader eventually learns, are actually just animals that have been mutated by radioactive fall-out).

It’s a very dated cover, but still a really cool one. Classic, one might say…

What Is It Like to be The Terminator?

I can’t believe it’s been 41 years since James Cameron’s The Terminator came out. I first saw it in the movie theater and like everyone else I was completely stunned by its energy and creativity. It might well be the best B-movie action film ever made. (Its sequel, T2, is an A-movie action flick that still feels like a B-movie, in a good way.) Cameron’s spin on what is essentially the ancient hunter-vs.-the-hunted plot—mashed up with about a dozen sci-fi tropes and a heaping serving of the Frankenstein/Dr. Faust myth—results in an almost perfect piece of entertainment. There is not a dull moment or lame moment in it. Every scene either surprises, shocks, or tickles the viewer.

The sequel, T2, is even better, mainly because it’s a coming-of-age film. Rather, it’s a becoming-human film. We watch as the Terminator observes human beings, learns from them, and begins to emulate their best qualities. It’s an archetypal story, and I (almost) tire of watching it. And, in the process of watching the film so many times over the years, I’ve repeatedly asked myself: What is it like to be the Terminator?

Continue reading “What Is It Like to be The Terminator?”Classic Sci-Fi Book Cover: “Lord of Light”

I’ve read a lot of trippy science books in my time, but Roger Zelazny’s Lord of Light is probably the trippiest. The only one that sort of comes close is Frank Herbert’s Dune, which makes a lot of sense considering both were written in the 1960s by two extremely smart and talented writers. (One of Zelazny’s other books, This Immortal, actually shared the Hugo Award with Dune in 1967.)

In fact, there’s not really a name for what Lord of Light is. Technically, it’s science fiction fantasy (a sub-genre I’ve written about before). That is, it looks and feels like a fantasy novel (as does Dune) until you realize that the plot has a sci-fi underpinning. Lord of Light is set on an alien world in which the population is stuck in a pre-industrial state, ruled over by gods of the Hindu pantheon. These gods interact with mortal humans on a daily basis, using magical powers and objects to control their destiny. Throughout the novel, however, Zelazny drops carefully crafted clues that the “gods” are actually the crew of a starship called The Star of India, which crash-landed on the planet centuries before.

These faux-deities use high-technology to set themselves up as gods, complete with a kind of immortality (they can transfer their consciousness to new, young bodies when the old ones wear out). They rule over the common people (who are revealed to be the descendants of the passengers of the ship) with an iron fist, doling out justice and retrobution from a floating, anti-gravity city (“heaven”). This reign is, ostensibly, for the people’s own good (tyrants always say this, right?). But when one of the last democratically-minded crew members, Sam, takes on the role of Siddhartha, he poses a threat to the status quo, which has kept humanity stagnant for generations.

This 1987 edition from Avon was the one I read in college, and I still own it. Its cover was done by an English illustrator named Tim White. I really like it because it captures that essential trippiness. At first, it looks like a pop-religion book, depicting figures dressed like Hindu gods. But what’s with the blue electric bolts? Or the floating city? And why is one of the Hindu “goddesses” blonde?

Ahhh, it’s really a sci-fi novel.

Yes, it is.