I started binge-reading science fiction when I was in 8th grade. That was the year that the local school board rezoned the kids from my White, suburban neighborhood to attend the largely Black, urban middle school, Lincoln, across town. This was a miraculous development for me because I had already attended Lincoln (back when my parents and I still lived in the ‘hood, or thereabouts), and I already loved it. But there was a downside—I had a really, really long ride on the school bus. Like almost an hour each way.

So, I started reading seriously, and as with a lot of boys at that age, my go-to genre was sci-fi. I read a lot of Arthur C. Clarke and Ray Bradbury and John Christopher. But perhaps the most revelatory, amazing book I had read up to that time was Larry Niven’s Ringworld. Never had a novel held such wonder for me, such a Tolkienesque landscape of adventure and possibility. The fact that Niven was able to pull this off in a book which is, even today, a prime example of so-called “Hard SF,” in which every story element must be grounded in, or acknowledge the effect of, some scientific principle.

The fact that Niven’s novel (the first of a tetralogy) has never been adapted to film is perhaps testament to this fact, the book’s off-the-chart nerd factor. Set in the 29th century, the story concerns an Earth-man, Louis Wu, who goes on adventure with two aliens and a human woman to visit a distant, recently discovered artifact called the Ringworld. It’s basically a giant, taurus-shaped space colony, so big that it wraps completely around its sun-like star. The entire ring spins to simulate 1G of gravity, and thousand-kilometer high mountains along the rim keep the air from leaking out. An inner ring of smaller, checker-box squares creates a shadow pattern on the inside of the big ring, creating a day/night cycle.

And there you have it, a plausible sci-fi world with normal gravity and a recognizable biosphere, including oceans, forests, deserts, mountains, and so on, but with an unbroken surface area equivalent to three million earths.

Oh, how this idea fired my thirteen-year-old imagination. Forget Shangri-La or Cathay or Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Mars or Middle Earth or any of the other fantasy lands of pre-1970s literature. Here was an endless realm that you could explore for a million years and never reach the end of. And, sure enough, as Louis and his alien comrades (one is a humanoid, Tiger-like creature called a Kzin, the other a two-headed cowardly alien called a Puppeteer) wander across the Ringworld, they encounter many of the tropes of 19th century adventure lit, including castles, galleons, savage tribes (including sexy native girls), shamans, sword-wielding heroes, etc. Niven accomplishes all this by establishing that the once high-tech inhabitants of the Ringworld have long since fallen into a pre-industrial state, leaving open the mystery of how this apocalypse happened and what remnants of the original civilization might remain, if any.

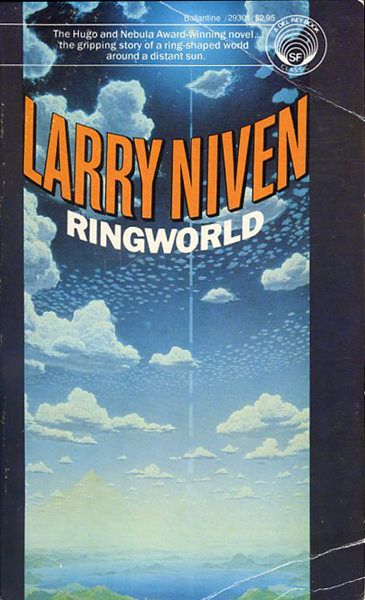

It’s a great, great adventure book, and it has inspired a number of fine covers. My favorite is the one above by Don Davis. Davis was in some ways an inspired choice since he was best known as a “space artist,” doing representations of proposed space colonies for NASA. (And, as I said above, the Ringworld is basically a giant space colony.) Davis’s cover captures the sense of wonder and endless possibility that novel creates, depicting a typical (summer-like) day on the Ringworld. In the distance, you can see the arc of the ring itself (the primitive inhabitants think it is an “arch”), complete with light-and-dark sections from the shadow squares.

It’s a fine cover, and I have no doubt that it and the book itself probably inspired the current obsession on the part of certain high-tech billionaires with the idea of space colonies, a possibility for a kind of endless utopia in outer space. And why not? Deep down, we’re all still thirteen-year-olds. Right?