The great film critic Roger Ebert once noted that the people we think of as heroes are those we looked up to when we were kids. As adults, we might admire a particularly talented athlete or actor or musician, but they won’t really be “heroes” to us; they’ll just be really cool (but life-sized) people.

I think that my middle-aged affection for Harlan Ellison might be a slight exception to this adage, however. I was a fan of his when I was growing up (he became famous in the 1970s with his revolutionary, sci-fi short-stories like “I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream”), but he wasn’t exactly a “hero” of mine. Then, in the 1990s, Ellison began to appear on TV as a talk-show celebrity, especially on the sci-fi channel, where he essentially co-hosted a show called Sci-Fi Buzz, where he was often very funny and always insightful. Also, to my amazement, one of his stories, “The Man Who Rowed Christopher Columbus Ashore,” was included in 1993’s Best American Short Stories collection. I saw an Ellison interview around that time, in which related that the series’ editor called him to give him the good news. At the end of their brief conversation, she asked him if had written any other short stories—an unintentional slight that Ellison said felt like “a dagger to the heart.”

But this was typical of Ellison’s relationship to the literary world, and to Hollywood. He couldn’t get no respect. Part of this life-long diss was, surely, his own fault. He was famously abrasive and out-spoken, and hated to have his work messed with. When he wrote the screenplay for the what is generally considered the best episode of the original Star Trek series, “City on the Edge of Forever,” he hated Gene Roddenbury’s changes so much that he tried to have his name taken off the credits. (Fortunately, he failed.) In fact, he was so contentious about such matters that he had a special pseudonym, Cordwainer Smith, that he would use when he felt his work had been to mangled by studio executives that he no longer wanted his real name associated with it.

Paradoxically, the more interviews I watched of Ellison in the 1990s and beyond, the more I liked him. He had a razor wit, and he did not suffer fools easily. He could also be mean as hell when he felt attacked. But these were all characteristics I had seen before in some exceptional people I have met over the years, including my great teacher, the writer Harry Crews. I never met Ellison, but I suspect that we would have gotten along just fine.

Indeed, I came to admire even Elllison’s famously pugilistic nature. He was quick to sue anyone who he felt had stolen his ideas. Most famously, he sued Orion Pictures over 1984’s The Terminator, alleging that director/writer James Cameron had cribbed the concept from a script Ellison wrote for The Outer Limits. Orion settled the suit out of court. (Cameron later called Ellison a “blood-sucking ghoul,” which I still find hilarious.)

Clearly, Ellison knew how to defend himself and his ideas, and to get what he felt was owed to him. Much of this toughness, I imagine, came from Ellison’s early life, growing up as an diminutive Jewish kid in Ohio. Like a lot of smart, little guys, Ellison learned how to punch back, and punch hard.

After I wrote a blog post about Ellison and Isaac Asimov last year, I found myself thinking about Ellison more and more. So much so, in fact, that a couple of weeks ago I decided to write something about him, although what form that would take.

Then, in one of those moments of synchronicity that happen to writers when they immerse themselves in a subject, I stumbled upon a fact regarding Ellison that I had never read before, and it came from a totally unrelated source.

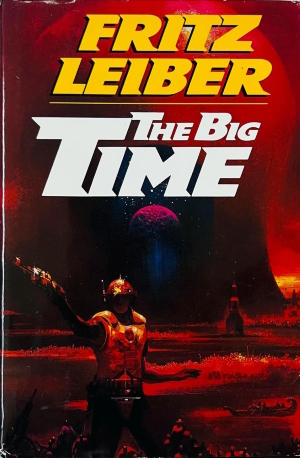

I was looking at some classic sci-fi book covers when I spotted one for Fritz Leiber’s The Big Time. I hadn’t thought of Leiber in decades (he was a favorite of a friend of mine in middle school), so out of pure curiosity I checked out his Wikipedia page. There, I was saddened to learn that Leiber spent the last few years of his life in poverty. As with so many writers, alcohol had taken its toll, and Leiber ended up living in a cheap motel. Apparently, Ellison came to visit him one day and was appalled by the state of his affairs, with Leiber not even able to afford a writing table. Rather, he was composing his latest work on a “manual typewriter propped up over the sink.”

Okay, maybe this wasn’t a good example of full-blown, Jungian synchronicity. I guess it wasn’t that unlikely that I should stumble upon a Ellison anecdote while reading about Leiber. They were both great science fiction writers, after all, and it make sense that they might have known each other. In fact, as I learned, Ellison included some of Leiber’s short stories in the Dangerous Vision anthologies that he (Ellison) edited for decades. Still, I didn’t know of any connection between the men. They were of different generations and circumstances, linked only by their genre and talent.

Unfortunately, the Wikipedia article does not cite the source of this (if anyone knows, please tell me), nor does it say what action, if any, Ellison took to improve Leiber’s circumstances. But I like to think that he did something to help. After all, he was a pugnacious, smart-ass little guy who looked after himself and other little guys. I miss him.

Here is a good interview that Ellison gave to the BBC in the 1970s.