When I was a public school kid back in the 1980s, I used to spend hours at the bookstore, mostly looking at science fiction books. It wasn’t just the stories themselves that interested me, but the cover art. Back then, before the internet gave one an endless supply of great sci-fi concept art of any kind, the only way to get one’s imagination going was to head to the bookstore.

So, it’s probably inevitable that I would regard that time as a golden age of sci-fi cover art. And I do. When I look at sci-fi books today, there is usually no cover art to speak of, but just an exercise in graphic design. The title goes in this font 38 point; the author’s name goes in this font at 28 point; etc.; with some blurry, abstract notion of an alien planet or a futuristic city. Back in the pre-digital days, sci-fi cover art consisted mainly of actual paintings, made by actual painters.

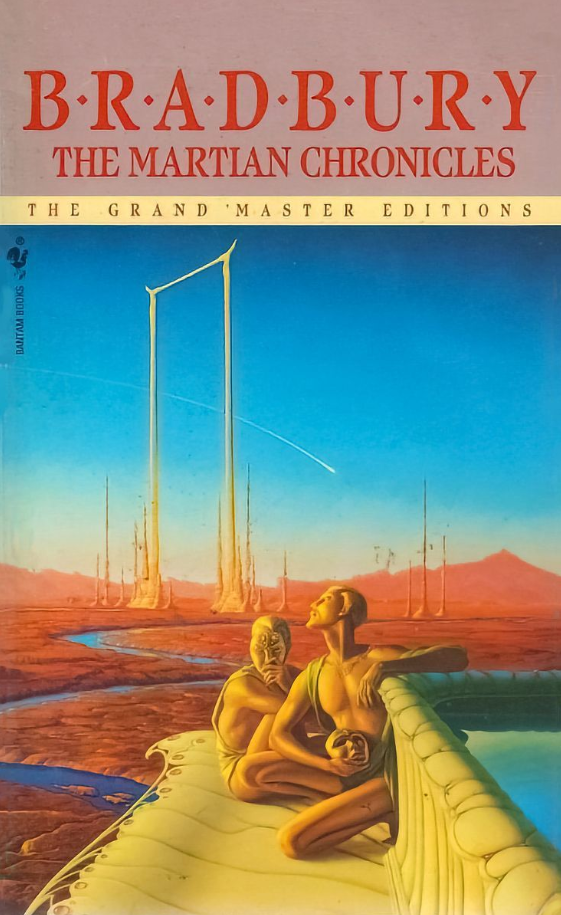

One of the best actual painters was (and is) Michael Whelan. His work has that perfect blend of realism, action, and whimsy that I always looked for in a good sci-fi cover. For five decades, he created some of the best covers ever made, and they earned him a place in the Science Fiction Hall of Fame.

One of my favorites is the one above, his cover for the 1990 Bantam/Spectra edition of Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles. If you haven’t read it (and you should), it’s an allegory about the loss of ancient wisdom, the horrors of capitalism, and even the conquest of the American West. Haunting the work are the ghosts of the Martians themselves, who once-great civilization is helpless in the face of the invading Earth-men, with their guns and disease and endless greed. I love this cover because it gives you a sense of that lost majesty, but it also makes you curious about the story.

In other words, it kindles the imagination.