I finally moved out of my parents’ house when I was twenty-two, when I embarked on a cross-country move to Tucson, Arizona. I had enrolled in an M.F.A. program at the university there, and I arrived knowing not a single, living soul. Once I found a place to live and acquired a U-of-A ID card, I spent my evenings going to the small, student gym in the basement of the football stadium, where I and a few other lonely souls (all dudes) worked out until the lights went off.

I vividly remember my first night at that gym. There were radio speakers in the ceiling tuned to the local F.M. rock station. That night, as it happened to be running an hour-long special devoted entirely to one rock album: Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours. The show included a few tracks off the album along with interviews with Lindsey Buckingham, Stevie Nicks, and Christine McVie. (For some reason, Mick Fleetwood and John McVie were left out.)

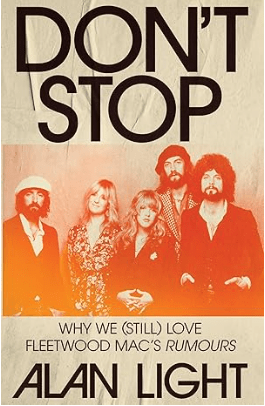

By this time, Rumours had already achieved legendary status of the sort afforded very few pop-music albums. (Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band is perhaps the only other.) Today, many years after that first night in Tucson, the album’s popularity and reputation has not diminished. If anything, it has increased. It’s gone from being a recognized artistic masterpiece to a timeless cultural colossus. As each new generation of music fans and musicians have discovered Rumours, an entire legendarium has been constructed around it.

Entire books have been devoted to the months-long, tortuous period in 1977 when the album was recorded. Two of the band’s members, John and Christine McVie, were in the midst of an ugly divorce. Two other members, Stevie Nicks and Lindsey Buckingham, were in the midst of an ugly breakup. And the remaining member, drummer and band leader Mick Fleetwood, was on the verge of breaking up with his famous wife, Jenny Boyd. The five members alternated between screaming obscenities at each other and slipping into effortless, soulful harmonies, all while drinking heavily and vacuuming titanic amounts of cocaine up their collective nose.

At one point late in the process, the album’s producer, Ken Caillat, was horrified to discover that the master recording tapes were literally flaking-out. They had been re-run through the mixing machines so many times that the metal-oxide strip was coming loose from the plastic, threatening to lose all the work he and the band had done. A technician from the manufacturer was flown in to manually transfer the recording onto a new tape before disaster struck.

In short, the fact that Rumours was made at all seems like something of a miracle.

Continue reading “What I’m Reading – “Dont Stop: Why We (Still) Love Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours””