I was very proud to see that Nole has an entry on Kevin Burton Smith’s excellent website The Thrilling Detective! Thank you, Mr. Smith!!!

I was very proud to see that Nole has an entry on Kevin Burton Smith’s excellent website The Thrilling Detective! Thank you, Mr. Smith!!!

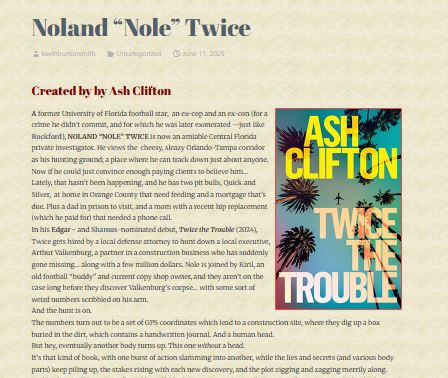

Went to Barnes & Noble’s yesterday and couldn’t resist finding my book and facing it out. (Yes, a cheap dopamine hit. I’m desperate.)

Apologies to Ann Cleeves, whose books I hid. (Only some of them, though!)

Recently I was chatting with a friend of mine, and at some point in the course of the conversation I told her about one of my favorite thriller novels of the last twenty years. It was Winter’s Bone by Daniel Woodrell, who sadly passed away in November. I described the plot to my friend, explaining how it’s about a 16-year-old girl, Ree Dolly, who lives in the Ozark mountains, raising her two little brothers. When her meth-dealing father goes missing, Ree faces the prospect of the bank foreclosing on the family mortgage, which would leave them all homeless (in addition to crushingly poor). To prevent this, Ree goes alone on a quest to find her father—or, at least, to find his body (she suspects he’s dead) so that she can get the money from his life insurance policy. This quest leads her into the mountain-shack domain of the local drug lord.

As I told all this to my friend, her expression became doubtful.

“Sounds dark,” she said.

I was taken aback, momentarily, and not just because my enthusiasm for Woodrell’s book failed to penetrate her skepticism. I was taken aback because I did not, in fact, have a good reply to her complaint. Yes, Winter’s Bone is a dark novel. Very dark. About as dark as you can get in a realistic, literary work. However, my enjoyment of the book is not dark. In fact, I remember the light-hearted, almost giddy thrill I felt while reading it—feverishly, tearing through it in a couple of days. It was the sensation that Vladimir Nabokov called a “kindling of the spine,” which one gets when reading a truly fine book.

What I found myself unable to communicate to my friend is the simple fact that I loved Winter’s Bone, even though its subject matter sounds like the stuff of an awful, depressing PBS documentary. How is this possible? Why do people like me sometimes read, and love, “dark” novels. More to the point, why do we read “heavy” novels in general—novels about tough subjects, adult circumstances, and big, real-life, consequential choices?

Why don’t we only read fun, predictable, pop-novels of the sort that dominate the best seller lists (not to mention the top 100 slots on GoodReads)?

I often think of something the late, great film critic Roger Ebert once said: “Happy movies don’t make you happy, and sad movies don’t make you sad. Good movies make you happy, and bad movies make you sad.”

Such a simple statement, and yet so profound! It applies equally well to novels. Good novels make you happy, and bad novels make you sad (or, at least, bored). Ultimately, though, Ebert’s aphorism is insufficient to answer my friend’s reaction. What does “good” mean in a movie, or a novel? For that matter, what does “happy” mean? Neither word seems easily definable, in this circumstance.

Happiness, in the grand sense, is not the sensation one gets from a book like Winter’s Bone. As thrilling and, yes, entertaining as it is, it does not induce true happiness. Rather, what it grants the reader is a sense of being transported—of movement, into the mind and world of the main character. That is, for each one- or two-hours session of reading the book, one becomes Ree Dolly. Take this opening paragraph:

Ree Dolly stood at break of day on her cold front steps and smelled coming flurries and saw meat. Meat hung from trees across the creek. The carcasses hung pale of flesh with a fatty gleam from low limbs of saplings in the side yards. Three halt haggard houses formed a kneeling rank on the far creekside and each had two or more skinned torsos dangling by rope from sagged limbs, venison left to the weather for two nights and three days so the early blossoming of decay might round the flavor, sweeten that meat to the bone.

What most people misunderstand about books like Winter’s Bone is that they are not merely well written. Yes, good writing is a necessary—but not sufficient—quality of a successful literary novel. What is also required, though, is this shift in psychic awareness. In the paragraph above, we feel Ree’s sense of life—her desperation, her determination to survive in the most severe physical circumstances. We, as readers, are right there with her, standing on the snow, freezing our butts off, wondering how we’re going to survive the winter.

In a later passage, we also get a sense of Ree’s love and compassion for her two little brothers:

Sonny and Harold were eighteen months apart in age. They nearly always went about shoulder to shoulder, running side by side and turning this way or veering that way at the same sudden instant, without a word, moving about in a spooky, instinctive tandem, like scampering quotation marks. Sonny, the older boy, was ten, seed from a brute, strong, hostile, and direct. His hair was the color of a fallen oak leaf, his fists made hard young knots, and he’d become a scrapper at school. Harold trailed Sonny and tried to do as he did, but lacked the same sort of punishing spirit and muscle and often came home in need of fixing, bruised or sprained or humiliated.

The great novelist Martin Amis once related Vladimir Nabokov’s belief that the reader should not identify with the character in a novel; rather, they should identify with the author. But I’ve never believed it. Yes, a good book does impart the wisdom of the author (this especially true in a masterpiece like George Eliot’s Middlemarch), as well as the benefit of their wit and depth of feeling. But that’s not the main reason people read novels. Rather, it is identification with the protagonist. And it’s not just that we identify with the main character; we must sympathize with them. We must participate in their struggle.

Even a rat-bastard character like Nabokov’s own Humbert Humbert—the most famous pedophile in literary history—could not keep our attention as readers if we did not, on some level, see ourselves in him. We must like him, if only a little. Feel sorry for him, even. Yes, he commits dreadful acts, but he does so, we sense, in a mistaken pursuit of happiness (that, what he believes is happiness, as he equates it to his sexual possession for Delores Haze). He is, in other words, a very wicked man but not a truly evil one.

Ree Dolly, of course, is neither wicked nor evil. She is, in fact, a completely valiant and admirable character. But that’s not the point. The relative morality or immorality of the main character is almost irrelevant. The only real requirement of a successful novel is that, through the art and skill and sympathy of the author, we are able to pierce the membrane of our own egos and enter that of the character. And, in doing so, we inevitably reflect upon our own, personal, real-life struggles. To paraphrase something I once heard Harry Crews say, it is a psychological truism that, in thinking about and judging a character in a novel, we inevitably come to think about and judge ourselves.

Right about now, you might be thinking of the Ancient Greek concept of carthasis, which refers to that paradoxical feeling of renewal one gets after watching a great, tragic play like Oedipus Rex or Othello. It is the sense of having participated in the plight of the tragic hero and come out the other side, as if reborn. And this idea certainly applies to literary novels. But what I am talking about is even deeper, more elemental, than catharsis. Rather, it has something to do with what Joseph Campbell described as “the rapture of being alive.” The rapture can, and in some ways must, transcend what we normally think of as decency or even morality. It goes deeper. It gets as who—and what—we really are, as beings that exist on both a physical and a spiritual plane.

So, I guess the title of this essay is a trick question. I don’t know why we read heavy, challenging novels. I don’t know why we enjoy them, and even need them. And I doubt anyone else really knows, either.

I just know that we do.

For some reason, I read a lot of science fiction during the holidays. Maybe this is because I loved science fiction as a kid, and I had more time to read it during the Christmas break. At any rate, this year I decided to post a list of great literary science fiction novels.

I’m not qualified to give a meaningful explanation of the difference between popular and literary fiction. My old professor, Jonathan Penner has already done that in his fine essay “Literary Fiction Versus Popular Fiction” (which I cannot find on the Internets, alas). But suffice to say that popular fiction is defined by a formula. As Penner states, “Every work of literary fiction seeks to be like none other; every work of genre fiction seeks to be like many others. Genre fiction works for effects on which the reader knows he or she may rely. Literary fiction always tries to see the world freshly.”

The novels I list below certainly fall into the category of popular fiction. They all make use of the common tropes of science fiction stories: space travel, robots, aliens, and the end-of-the-world. So why do I call them literary? Because each one of them, while remaining on a generic level, is centered around a vivid and successfully realized characters. Also, each is written with a emphatic artfulness and grace.

So here’s the list:

The Left Hand of Darkness Strangely enough, I first got interested in Ursula K. Le Guin’s classic novel when I read a review of it by John Updike. It’s about a human envoy who is sent to a distant alien planet called Gethen. Gethen is remarkable not only for its isolation, but also because the locals, although descended from homo sapiens thousands of years of previously, are all hermaphrodites. Specifically, they function as men for certain part of their lives, and as women for the other. It sounds a bit hokey now (the plot was even ripped-off on an episode of Star Trek), but it’s a fine little novel, with some genuinely compelling drama. (It actually develops into a kind of wilderness adventure story when the main character gets entangled in the political intrigue of the Gethen government.)

Lord of Light Roger Zelazny was a hell of a good writer who is best known for his Chronicles of Amber series of fantasy novels. But my favorite is Lord of Light, which is the first novel I ever read that seems, at first, to be one genre (religious fantasy), but then reveals itself—convincingly—to be another (science fiction). Zelazny sets the story on an unnamed, earth-like planet where the gods of the Hindu pantheon (Brahma, Vishnu, Shiva, etc.) are real and very much alive. These dieties use their Godly powers to rule over a pre-literate culture of peasants (controlling them in ways that are often less-than-divine).

The story centers on Sam—who closely resembles Gautama Buddha but with a Marlowesque twist—who is trying to unseat the vain and profligate Gods from their position of power. Sam, we soon learn, is one of the original crew members of a starship called The Star of India, which crash-landed on the planet eons previously. Apparently, Sam and the other surviving officers used their technology to set themselves up as “gods” to rule over the other castaways, and eventually came to believe their own propaganda. It’s a far-out idea, which Zelazny delivers in a surprisingly subtle, vivid novel that is part epic, part spoof.

Virtual Light I think William Gibson is one of the best writers of his generation, literary or otherwise. He invented the term cyberpunk, and its attending genre, of which Virtual Light is my favorite example. It’s about a young bike messenger, Chevette, who spends her day cycling through the teeming, corporate-ruled streets of a future San Francisco. In a plot twist that is almost Dickensian in its lyricism, Chevette accidentally comes into possession of a very unusual pair of computerized sunglasses, which a villainous corporate hit-man is very anxious to get back. Gibson is a genius at mixing high-tech plots with low-tech heroes, and Chevette soon has to take refuge in an underground, DIY society based on the remnants of the Oakland Bay Bridge.

The Martian Chronicles Okay, it’s a stretch to put this one on the list, not because it isn’t literary, but because it really isn’t science fiction. It’s actually a collection of interlocking fables, all of which are based on Mars during the early phases of its colonization. Unfortunately, the planet is already occupied by an ancient race of Martians. If you substitute Illinois for Mars and the Sioux for the Martians, you get an idea of the feel of this novel, which Bradbury himself said was inspired by Sherwood Anderson’s classic collection, Winesburg, Ohio. Many of the stories are genuinely beautiful and haunting.

The Tripods If you didn’t read Samuel Youd’s trilogy when you were a kid, you should do so now, especially if you have a kid of your own. Earth has been conquered by aliens, and what remains of humanity exists in a servile, pre-industrial society. Young Will and his cousin Fritz escape their village and go on a quest for the fabled “White Mountains” where a human resistance is forming.

A Clockwork Orange The movie has outshone the book for most of my lifetime. But the book is actually better, written in the inimitable voice of Alex, a fourteen-year-old sociopath who is just trying to have a good time in an Orwellian England of the near future.

God Emperor of Dune The original Dune is a really cool adventure story. I always thought of it as Lawrence of Arabia in the 30th Century. But I think Herbert’s fourth novel in the series, God Emperor of Dune, is the best, from both a narrative and stylistic point-of-view. It focuses on just a couple of characters (as opposed to dozens) and it presents Leto Atreides (son of Paul) as genuinely sympathetic character.

Nova Samuel R. Delany could never decide whether he was a physicist or a mythologist or an literary fiction writer. Why limit yourself? Nova, the story of a mad space-captain seeking to fly through the center of an exploding star, is Delany’s tightest and most interesting novel.

Childhood’s End I hesitate to put this one on the list. I loved it as a kid, as I loved all of Arthur C. Clarke’s books. As a writer, he was very, very limited. But in Childhood’s End, he really outdid himself. It’s the first novel I ever read that broached the concept of a technological Singularity.

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep I can’t help but think that, in some alternate universe much like those he described in his novels, Phillip K. Dick is alive and well and living as a respected and beloved literary fiction writer. In this universe, however, he wrote mesmerizing, almost hallucinogenic sci-fi novels about good and evil, the definition of “reality”, and what it means to human. His best book, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, is a haunting classic.

Author’s Note: This post first appeared some years ago on my old blog, Bakhtin’s Cigarettes.

As part of the work for the Read a Classic Novel…Together channel, I’ve been reading a very old classic indeed, The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman (almost always abbreviated to just Tristram Shandy). Published by Laurence Sterne in 1767, it’s a very funny, sly book—kind of like Curb Your Enthusiasm, but in the 18th Century—and I found myself imagining George Washington reading it (and laughing his ass off) while holed up in some winter bunker during the dark days of the American Revolutionary War.

The story is told by Shandy himself, a very smart but self-absorbed and neurotic man (again, a lot like Larry David) who tells his life story in wry, sardonic, and occasionally schizophrenic prose. At one point in his rambling narrative, he mentions the “seven planets” in the heavens, which surprised me. Sure, I knew that even the ancient Romans knew about the inner planets, as well as Jupiter and Saturn. But the fact that the unfathomably distant Uranus was known in the 18th Century struck me as remarkable.

As it turns out, I was wrong. Uranus was not discovered until 1781, over a decade after Sterne wrote his novel (but still much earlier than I thought). Which means that there is no way that either Sterne, the writer, nor Shandy, the character, could have known about the actual seventh planet.

So, what, exactly, is Shandy alluding to in the “seven planets” bit? It seems that he was referring to the astrological planets in their classical (and very unscientific) sense, i.e., the Moon, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. This context makes sense, in retrospect, because Shandy is obsessed with astrology and its supposed effect on a person’s character. (Yes, he’s a bit of a kook.)

By the time I sorted all this out, however, it was too late; I was already deep down the Wikipedia rabbit-hole. I looked up the history of the outermost planet (not to be confused with the dwarf planets like Pluto and Ceres), Neptune. Neptune was discovered by French astronomer Urbain Le Verrier in 1846. Not only was it the first planet to be discovered entirely by telescope, it was also the first one whose existence was surmised before it was actually observed. That is, Verrier and fellow astronomer John Couch Adams had noticed irregularities in Uranus’s orbit, which, they suspected, might be caused by a seventh, hitherto unseen planet. They then deduced the probable location of this hypothetical planet and hunted it down.

And that’s not all! I also learned that Neptune was actually discovered before it was discovered. As historians found later, Neptune was seen at least three times before, by Galileo Galilei in 1613, Jérôme Lalande in 1795, and John Herschel in 1830. Each of these men recorded seeing something in that spot, but none of them realized it was a planet and not just a weird “fixed” star.

Apparently, this sort of thing happens with some frequency in the world of science, to the point that it actually has a name: precovery. In a precovery, someone finds all the information they might need to make a real (and potentially career-making) discovery, but they never put the pieces together. (Or, at least, they never publish a paper about it.)

I think there might be a profound lesson here about the difference between data and knowledge, observation and understanding.

It’s also a lesson about publishing what you’ve got, ASAP. Before some other doofus steals your thunder.

Just a heads-up…. My Edgar-nominated and Shamus-winning novel, Twice the Trouble, is a Kindle Deal all this month. You can get the ebook for just $1.99. That’s less than half the price of a Starbucks’ latte (and it will last a lot longer)!

I know, I know. This cover is a bit out-there. Not every sci-fi book cover, after all, has a spaceship hovering in a night sky over a plus-size female model in a metal bikini, go-go boots, and mail headdress. (But I kind of wish they did.)

Even so, this cover for Babel-17 by Samuel R. Delany is a bonafide classic by the great Spanish illustrator Vicente Segrelles, who has created a ton of great covers throughout his long and brilliant career. It was done for a series of Delany’s novels that were re-released by Bantam in the 1980s, all of which had great, subtle, off-beat covers.

Now, I’ve read a lot of snark about this cover on various chat-boards. Younger guys, especially, find it hilariously bad (and perhaps a lot of girls, too). I think this is because the woman depicted is not the usual, skinny, spandex-clad sci-fi babe. Personally, that’s one reason I like her. I think she’s mysterious, regal, and (yes) sexy.

More importantly, she captures the essence of the novel’s main character, Rydra Wong, who is not only the captain of a spaceship but also a master linguist. When government operatives seek her help in cracking an enemy, alien code called Babel-17, she discovers that it is not just a code—it’s an entire language. She promptly sets-off on a space-adventure to decipher the language, a quest that leads her into a war zone on the edge of the galaxy.

One of the things I love about Babel-17 is the way Delany, even way back in 1966, managed to push a message of tolerance and multi-culturalism. Wong’s spaceship is crewed by a rag-tag group of mercenaries, some of whom are not only transsexual but transhuman, opting for synthetically altered bodies that make them resemble wild animals or fairy tale creatures, and so on. Moreover, Wong’s desire to find the source of Babel-17—and, thus, better understand the aliens who are attacking humanity—suggests a deeper response to the usual fear and xenophobia that was so endemic in America at the time (and is again now, alas).

Babel-17 a classic sci-novel with a classic cover. Check it out…

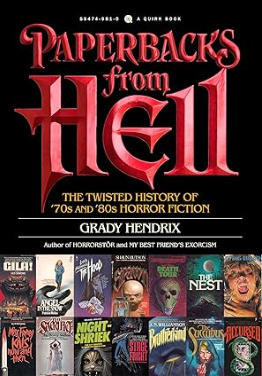

Having had exactly one book traditionally published, I am far from an expert on the world of publishing. Even so, I learned a lot more than I ever expected, and have since become fascinated by the industry as a whole. Also, I am currently working on a supernatural horror novel. So, it makes perfect sense that I would be drawn to Grady Hendrix’s excellent non-fiction book, Paperbacks from Hell, which examines (skewers?) pulp horror literature as it existed in the 1970s and 80s, both as a uber-genre and as an industry.

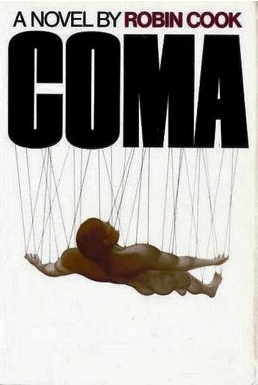

Let me say right up front that this is a very funny book. I found myself laughing out loud many, many times as Hendrix describes the trends and fads that overtook the genre. Take this passage where he introduces the wildly successful pop writer Robin Cook, whose 1977 book Coma is, in Hendrix’s words, the “source of the medical-thriller Nile.” As Hendrix goes on:

It all started with Robin Cook and his novels: Fever, Outbreak, Mutation, Shock, Seizure…terse nouns splashed across paperback racks. And just when you thought you had Cook pegged, he adds an adjective: Fatal Cure, Acceptable Risk, Mortal Fear, Harmful Intent. An ophthalmologist as well as an author, Cook has checked eyes and written best sellers with equal frequency. He’s best known for Coma (1977)…. Its heroine, Susan Wheeler, is one of those beautiful, brilliant medical students who’s constantly earning double takes from male colleagues or looking in the mirror and wondering if she’s a doctor or a woman—and why can’t she be both, dammit? On her first day as a trainee at Boston Memorial, she settles on “woman” and allows herself to flirt with an attractive patient on his way into a routine surgery. They make a date for coffee, but something goes wrong on the table and he goes into…a COMA!

Hendrix cleverly divides each chapter to a single, overarching trend in the pulp horror universe, with titles like HAIL, SATAN (novels of demonic possession and devil-sex), WEIRD SCIENCE (evil doctors and mad scientist-sex), INHUMANIOIDS (deformed monsters and mutant-sex), and so on. I was especially impressed by the way Hendrix explains each publishing fad as a symptom of a larger societal shift. For example, he explains how the white-flight phenomenon of the 1970s in which white middle- and upper-class families abandoned the big cities and moved to quaint, charming little towns in upstate New York or the mid-west or norther California or wherever, results in a surge of small-town horror novels like Harvest Home (wherein evil pagan matriarchs conduct human sacrifices to make the corn grow) and Effigies (wherein Satan is breeding grotesque monsters in the basement of the local church).

Another chapter entitled CREEPY KIDS, which deals with such diverse plot concepts as children who are fathered by Satan, children are who are really small adults pretending to be children, and children who, for whatever reason, just love to kill people. I particularly love this passage:

Some parents will feel helpless. “How can I possibly stop my child from murdering strangers with a hammer because she thinks they are demons from hell?” you might wail (Mama’s Little Girl). Fortunately there are some practical, commonsense steps you can take to lower the body count. Most important, try not to have sex with Satan. Fornicating with the incarnation of all evil usually produces children who are genetically predisposed to use their supernatural powers to cram their grandmothers into television sets, headfirst. “But how do I know if the man I’m dating is the devil?” I hear you ask. Here are some warning signs learned from Seed of Evil: Does he refuse to use contractions when he speaks? Does he deliver pickup lines like, “You live on the edge of darkness”? When nude, is his body the most beautiful male form you have ever seen, but possessed of a penis that’s either monstrously enormous, double-headed, has glowing yellow eyes, or all three? After intercourse, does he laugh malevolently, urinate on your mattress, and then disappear? If you spot any of these behaviors, chances are you went on a date with Satan. Or an alien.

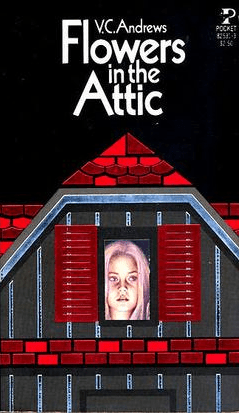

One the many things I learned from reading the book was how the entire publishing world (not just horror) was permanently changed in 1979 by an obscure tax-law case called The Thor Power Tool Co. v Commissioner. In this case, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that manufacturers could not write-down poor-selling or slow-selling inventory and thus reduce their tax liability. The case was focused on unsold parts for power-tools, but the ruling equally applied to publishing houses, who had hitherto done the same kind of write-down on their slow-selling novels. As Hendrix explains: “Suddenly, the day of the mid-list novel was over. Paperbacks were given six weeks on the racks to find an audience, then it was off to the shredder.” And so, inevitably, came the frantic scramble to find those half-dozen or so “blockbuster” books each season, behind which publishers focused their resources. (A similar “blockbuster” effect ravaged Hollywood in the 1970s, in this case due to the success of summer films like Jaws and Star Wars.) Books got less pulpy and more sparkly, with foil covers and die-cast cutouts like those made famous by the V.C. Andrews novels (which continued to be published, zombie-like, long after Andrews’s death).

Whether you’re a writer or just a pulp-paperback fan, Paperbacks from Hell is a great read. Check it out…

I’m very happy to announce that my short story, “Cerulean”, has been published by Killer Nashville Magazine! Many thanks to Isabelle Kanning and the rest of the editorial staff for accepting it.

Check it out if you have time. It’s free to read…

The most important novel in the dystopian science fiction sub-genre is George Orwell’s 1984. The second most important is Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange. I would go so far to argue that Burgess’s book has, in some ways, been even more influential and culturally significant than Orwell’s, especially for those generations that grew up in the 1970s and later.

It was in 1971 that Stanley Kubrick adapted the book into a landmark film, which was how I first discovered the novel. By the time I was a teenager, in the early 80s, Kubrick’s movie had taken on cult status—almost as much as 2001: A Space Odyssey. My friends and I all loved the movie. And I, being a particularly bookish kid, decided to check the novel out, too.

The secret to A Clockwork Orange’s success, topping that of almost all other dystopian novels, is that it has a great, exciting twist. Its protagonist, a fifteen-year-old delinquent named Alex, seems more like a villain than a hero. He is, after all, a thug, a thief, a gang-member, a rapist, a drug user, and a lover of all things violent (“ultraviolence,” as he and his gang friends call it). Yet, in comparison to the oppressive, authoritarian, end-stage-Capitalist society in which he lives, he is a kind of hero. Against that iron-grey backdrop, his better, human qualities come to the fore—his intelligence, his ferocious courage, and his absolute dedication to personal pleasure, the state-be-damned.

This twist is one of the greatest, central ironies in modern literature, and it’s the reason teenage boys (and probably a few girls, too) continue to find themselves drawn to the book, just as they have been for sixty years. Conversely, this is also the reason that social conservatives have hated the book for just as long. In fact, as I recently learned from openculture.com, A Clockwork Orange was the most banned book of the 2024-25 school year.

I have no doubt that Burgess would have been very, very proud.

Kubrick’s film version was so powerful that it influenced the cover-design for most subsequent editions of the book. Many of these covers were thinly-veiled riffs on the movie poster or on Malcolm McDowell’s brilliant performance, wearing his singularly perverse, false-eyelash. I really like this cover from 1995 by Robert Longo because it bucked that trend and did something new.

Also, I think it really captures the madness of the book—the ferocity of Alex’s character as he rages against the machine. Yes, he’s an evil character, but that’s sort of the point of the whole book. Alex has a God-given right to be evil, if that’s his choice. Evil is an implied, but not a necessary, product of his free will, and he fights valiantly against being “programmed” by the cold authority figures of the story.

Just like most teenagers. Even the ones that aren’t psychopaths.