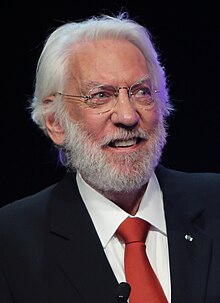

I really enjoyed The Hunger Games movies when they came out. Not only were they great examples of dystopian science fiction, but they served as a refresher course in the nature of fascism. The main baddie in the films was, of course, President Snow, played with great menace and understatement by the great Donald Sutherland.

I am very grateful to the producers of The Hunger Games for introducing Sutherland to a new generation of film lovers, especially at a time when his career was in a bit of a lull. Sutherland was one of my favorite actors when I was growing up, best known for career-making roles like Hawkeye Pierce in M.A.S.H., Oddball in Kelly’s Heroes, and the titular role in Klute. One of the great ironies of film history is that Sutherland should now be so closely associated with the role of President Snow—literally a right-wing fascist dictator—when his early, defining performances were usually as lovable, left-of-center antiheroes (Hawkeye Pierce especially).

Sutherland was one of the few movie stars from the 70s and 80s to have curly, hippie-hair, and his entire persona seemed to be that of a counter-cultural smart guy. The Alpha-Hippie that all Beta-Hippies aspired to be. I say he was a smart-guy, and it’s true—never did an actor so effortlessly exude intelligence, even without dialog, as Sutherland did. But while he was so obviously a smart-guy, he was never a smart-ass. Even the irreverent Hawkeye Pierce—perhaps the most famous prankster in cinema history—reserved his mocking for when he needed it to retain his sanity, and focused it on those who most deserved it.

One of the best ways to understand Sutherland as an artist is to imagine his stylistic opposite, Nicholas Cage. Like Sutherland, Cage is a brilliant actor, and a very smart guy, but while Cage is famous for his artistic daring, often taking his performances to frenetic heights that would seem ridiculous for other, lesser actors, Sutherland was known for his almost impenetrable reserve. He always seemed to be holding something back, in a good way. He kept the viewer guessing about what was really going on behind those crystalline blue eyes.

Perhaps my favorite Sutherland role when I was growing up was as a world-weary health inspector in Philip Kaufman’s 1978 sci-fi horror masterpiece The Invasion of the Body Snatchers. In this film, Sutherland almost drips existential cool, even when faced with an invasion of alien pod-people (read: communists, right-wing conformists, or your boogey-men of choice) who want to eliminate humanity.

Check it out.