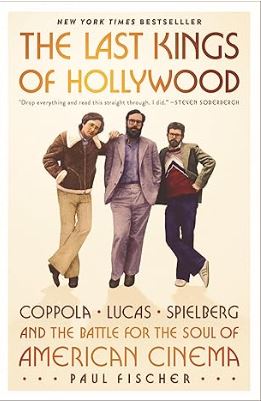

I’ve been reading an excellent non-fiction book by Paul Fischer called The Last Kings of Hollywood: Coppola, Lucas, Spielberg—and the Battle for the Soul of American Cinema. It’s very similar to another great book I read recently (and subsequently wrote a post about), Don’t Stop: Why We Still Love Fleetwood Mac’s “Rumours,” in that both books document the history of struggling artists—film directors, in the former, and rock stars, in the latter—who hit the Big Time. Inevitably, they each also tell the story of a bohemian sub-culture of the 1970s, when people lived hand-to-mouth in the canyons of Southern California, occupying cheap, hardscrabble houses and doing menial jobs while they developed their artistic skills. They also did a lot of drugs (mostly cocaine, booze, and marijuana) while having lots of sex with multiple partners. Fischer’s book, in particular, tells the great story of aspiring actress Margo Kidder, whose rented, A-frame house was frequented by young film makers, actors, musicians, and other arty-types, all attracted by Kidder’s good-natured wit, excellent cooking, and general hospitality. And by her beauty, of course. As Fischer relates, Kidder once joked that if she had bothered to write a memoir of that halcyon time, she would’ve entitled it I Fucked Everybody.

Such artistic, bohemian scenes are as old as…well, 19th Century Paris, when the term “bohemianism” came into use. Apparently, it first referred to the Romani people of Paris, who lived a nomadic existence doing odd-jobs and performing various services (most legal, some not) for local people. In French, they were called bohémiens, because they were thought (mistakenly) to have migrated to France from the Kingdom of Bohemia. Bohemian soon came to describe anyone who, by choice, lived an unconventional life on the edges of society, doing as they pleased. Often, these were artists (painters, writers, musicians) who refused to pursue a normal career, but it also included the moneyed, free-spirited offspring of rich people, who went “slumming” with those same artists.

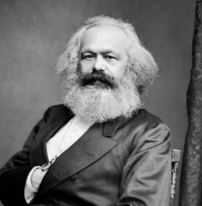

As I was reading the Wikipedia page on bohemianism, I discovered that such bohemian subcultures are often examples of a precariat. Precariat (I learned) is a mashup of precarious and proletariat, the latter being Karl Marx’s term for the working class. (“Proles” as they are called in George Orwell’s 1984.) People in a precariat are usually just as poor but also lack even the job security of the traditional industrial class, going from low-paying job to low-paying job, with no guarantee of when they’ll land their next position (or be able to pay the rent).

The term (I also learned) is particularly apt today, being often used to describe our modern world of Uber drivers, digital freelancers, and other non-traditional workers. As I read about all this, I thought of a book I posted about some years ago called Nowtopia: How Pirate Programmers, Outlaw Bicyclists, and Vacant Lot Gardeners Are Inventing the Future Today! by Chris Carlston. Written at the dawn of the so-called gig economy, Carlston describes how, rather than dreading the precariousness of modern capitalism, some people have embraced it. By working temporary gigs, such people—whom Carlson calls Nowtopians—have managed to preserve the time and freedom to pursue their true passions like art, or education, or community service, or whatever. He writes:

What we see in the Nowtopian movement is not a fight for workers emancipation within the capitalist division of labor…. Instead we see people responding to the overwork and emptiness of a bifurcated life that is imposed in the precarious marketplace. They seek emancipation from being merely workers. To a growing minority of people, the endless treadmill of consumerism and overwork is something they are working to escape. Thus, for many people time is more important than money. Access to goods has been the major incentive for compliance with the dictatorship of the economy. But in pockets here and there, the allure of hollow material wealth, and with it the discipline imposed by economic life, is breaking down.

Looking back on these words now, they seem a bit naïve. The longings of a utopian dream. They hardly seem describe our current gig economy, which, instead of new bohemian class, seems little more than a last-ditch means of survival for those who can not find good, decent-paying jobs (with benefits). As wealth and power become more concentrated in the hands of a few (usually male) oligarchs, fewer people have the freedom to do anything, no less pursue art. They’re too busy working, looking for jobs, looking for housing, or generally getting by.

In fact, rather than a utopia, our precariat seems more like the dystopia of which William Gibson foretold in his early, cyberpunk novels. Worlds in which most people on earth are underemployed, rootless, and in constant danger, while a tiny middle-class manages everything for an even tinier upper-class. The heroes of such novels are usually young, smart people who resist in the only way they can—by entering an underworld of artists, hackers, thieves, and gangsters who make their living off the rich.

Does this mean that we, as modern Americans, are headed for a world in which the precariat is, essentially, everyone? I think so, yeah. After all, isn’t that the fantasy of every oligarch—to rule over a vast sea of unpaid serfs with no autonomy to control their own lives? A limitless, self-perpetuating underclass, with no agency to defend themselves from the predatory impulses of the ultra-rich, impulses are, ultimately, sadistic in nature.

I hope not. We’ll see.