** SPOILERS BELOW **

The better part of a decade has passed since Jordan Peele’s landmark horror film Get Out was released, marking Peele’s transformation from famed comedy writer and sketch artist to one of the most important filmmakers of our time. Peele has since added two more films to his horror oeuvre—2019’s Us and 2022’s Nope.

All three are great, but my favorite is Us. For me, it hits on the deepest and most disturbing level, and it has the richest palette in terms of effects. It’s also the hardest to figure out in terms of plot. With Nope and Get Out, the viewer has a vague sense of what’s going on, even early in the film (although the details turn out to be more shocking and terrifying than anyone suspected). But while watching Us, I was totally mystified. I knew it had something to do with evil twins—true doppelgängers in both the literal and the psychological sense—but I had no real idea of what the actual plot would turn out to reveal. And what a reveal it is!

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Part of Us’s appeal lies in its slow-burn first act. (This is true of Get Out and Nope, too, but Us takes it to the next level.) The movie starts with a flashback to 1986, when a little girl, Adelaide, breaks away from her bickering parents at a beach boardwalk and finds a strange funhouse. It’s a simple premise, yet so much disturbing stuff going on in this segment that it’s almost impossible to describe. We have the tension between the parents, raising the specter of divorce (the thing most kids fear more than anything else except death). Then we have the separation of the child from the parents (another primal fear). And, finally, we have the freakish funhouse, which, though apparently deserted, is still lit with eerie neon light.

This is the film’s first (of many) instances of the haunting power of liminal space. That is, places that should be crowded with people but are empty instead. When Adelaide walks into the empty funhouse, I was reminded of those times as a kid when I visited my school at night (usually for some club meeting) and I was mesmerized by the emptiness and silence of the hallways and classrooms. There is something inherently fascinating and yet unnerving about such vast, empty spaces. I think it has something to do with object permanence, that developmental stage that all toddlers go through in which they realize that things don’t cease to exist just because we can’t see them at that moment (thus making peek-a-boo a really pointless game). On some level, we never really lose the feeling of dread that we all experience when we realize that things have their own, ghostly existence at night, or on the weekend, or in other periods of disuse. We can’t help but suspect that someone must be in those spaces, even at night—some other set of kids who attend school on the night-shift, perhaps. Evil kids, we suspect, who might be versions of ourselves.

This is literally what happens to the protagonists of Us—they meet their evil doubles. And, indeed, those doubles seem to inhabit a liminal, doubled version of a giant school, complete with lockers and classrooms. And it is freaky as hell.

After a terrifying encounter with her twin, Adelaide returns to her parents but seems traumatized. The story then jumps to the present day, in which the grown-up Adelaide is going on vacation with her husband, Gabe (wonderfully played by Winston Duke), and their children, teenager Zora and ten-year-old Jason. The vacation is set for a sleepy beach town (with a boardwalk almost identical to the one at the film’s opening scene), where Peele drops numerous, disturbing hints that something is quite wrong with the general populace. And, sure enough, the family’s vacation home is attacked that evening by their doppelgängers—evil, sadistic zombies who are on a terrifying mission.

The most disturbing of these is Red, Adelaide’s twin, who speaks in a raspy, witchlike voice. She explains that the twins are “tethered” to their day-world counterparts, and apparently the only way to “untether” themselves is to kill their twins. (They each have a pair of big, metal scissors with which they intend to perform this grisly act.)

Carl Jung was one of the first psychologists to write about the concept of the shadow—the subconscious, dark version of the self that every person has. Typically, this shadow-self harbors all the pain, resentment, and guilt that our conscious selves suppress beneath the level of awareness. It’s a powerful idea, and never has it been more fully realized than in Us. In the movie, each member of Adelaide’s family meets their shadow-self, literally, as embodied in the Tethered. I especially like how Peele gives their Tethered versions their own names—Red, Abraham, Umbrae, and Pluto, respectively—thus reinforcing the idea of the shadow as autonomous identity.

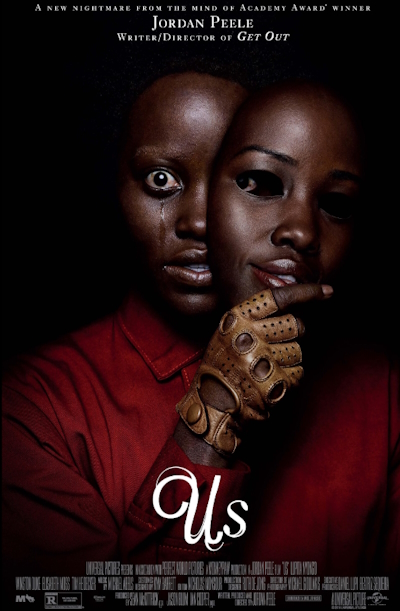

It’s heavy stuff. Yet it would all fall apart, dramatically, if not for the brilliant acting of all the players, especially Lupita Nyong’o. It’s hard to imagine a more challenging acting job, technically, than that of playing Adelaide/Red—two characters who are not only polar opposites morally but one of whom speaks in a ravaged, destroyed voice. (The execution of this voice threatened to damage Nyong’o’s “normal” voice, thus making her unable to play Adelaide.) And, of course, these twinned characters have to play against each other in the same scene, meaning Nyong’o had to imagine herself in each scene.

And, in a really intense, psychological horror film like Us, you’ve got to have some comic relief. This is ably provided by Winston Duke as Adelaide’s lion-hearted by goofy husband, and by Elizabeth Moss as Adelaide’s hilariously shallow friend. But, let’s face it, Us is Lupita Nyong’o’s movie. She carries it. Her performance is a great achievement, and one that should have garnered her an Oscar nomination for Best Actress. (Nyong’o already has a Best Supporting Actress Oscar for 2011’s Twelve Years a Slave.) But, of course, there is no justice in this world—which is also, as it happens, one of the major themes of the movie. The Tethered, we learn, are kept prisoners in vast, underground labyrinths by the government. (What purpose they serve is never made clear.) This makes them a great metaphor for class inequality and economic servitude. After all, we as Americans do have unseen, disposable people who labor for us in dark prisons. (We call these prisons “sweatshops,” and most of them are in Asia.)

But that’s a subject for another post…