When I was a kid, my parents bought me a book called A Pictorial History of Science Fiction by David Kyle, which covers the history of science fiction illustration from Jules Verne all the way through the 1970s. (The book was printed in 1976.) I still have it. I remember being especially enthralled by covers from pulp magazines in the 1930s like Astounding Science Fiction and Amazing Stories. Many of these covers were devoted to some artist’s vision of The City of The Future—usually some towering, high-tech, hive-like metropolis.

It makes sense that sci-fi nerds of the 1930s would imagine a vertical, urban future. At the time, the most sophisticated places on earth were the great western cities of Europe and America. Paris. Berlin. And especially New York—Manhattan—with its great skyscrapers reaching ever higher. The obvious extrapolation of this trend was that someday everyone would be living in some vast, super-tall version of New York or Los Angeles, with buildings hundreds of stories high and millions of people living in close proximity. Ramps and walkways would connect these towers in the sky, allowing residents to hardly ever venture down to street-level. Airplanes, blimps, and elevated high-speed trains would speed residents from one end of the city to the next.

For most of these sci-fi artists and writers, this was going to be a good thing. A utopian vision, in fact. Future cities would be paradises of high technology, dense but egalitarian. Robots would do all the dirty work, and everyone would be rich. For others, though, the City of the Future would be a capitalist hell, with the decadent rich living high above the exploited poor. These upper-classes would hoard resources and technology, either out of fear or greed or sheer meanness. It is this dystopian vision that informs works like Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, as well as every instance of the cyberpunk genre from William Gibson’s Virtual Light to Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner.

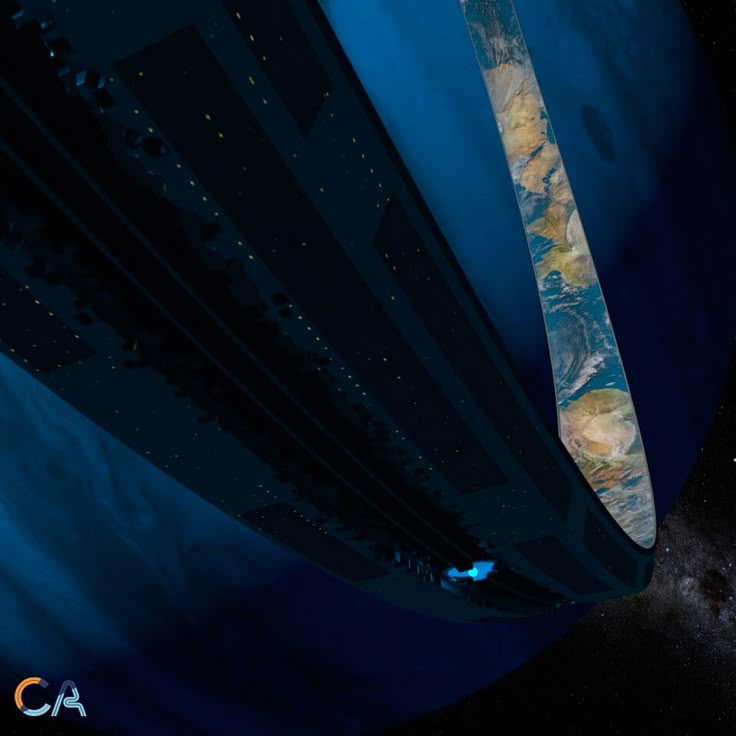

Despite this dark side, however, the vision of an artificial, high-tech utopia has long existed in sci-fi, and it still does today. But the vision itself has changed. Relocated. These days, the City of Future is almost invariably depicted as being in outer space—”off-world,” in the lingo of movies like Blade Runner—either on a nearby planet or the moon or on a station floating in space.

Space stations, in particular, have captured the imagination of science fiction fans for the past four decades, ever since Princeton physicist Gerard K. O’Neill published The High Frontier: Human Colonies in Outer Space. In that landmark book, O’Neill explained the advantages of living on a space colony as opposed to a land-based colony like Mars or the moon. These include the fact that one could spin the colony to produce the same gravitational pull as Earth, thus avoiding any physiological problems the colonies might suffer from living on a smaller world. Unlimited solar power is another plus, as is the fact that, living outside the gravity well of a planet or moon, travel between colonies would be vastly cheaper. Trade would thrive, fueled by a steady flow of cheap, raw materials from the asteroid belt and various moons throughout the solar system.

O’Neill was the first, legit scientist to take the idea of people living in outer space seriously, and he was able to back up his ideas with hard data, including actual blueprints for working stations. Namely, he invented the O’Neill Cylinder, a tube-shaped world the size of a city with its residents living on the inner surface. Other designs were created by a diverse group of like-minded theorists. Of these, the most compelling is the Stanford torus (named for the university where the plan was cooked up). Instead of a tube, it’s a giant wheel. For whatever reason, it’s this ring-like design that has dominated most sci-fi stories of recent decades. Larry Niven’s Ringworld is basically a humongous Stanford torus (large enough to encircle a star). And the design is also represented in the wheel-worlds of the Halo videogame franchise and the fabulous Orbitals of Iain Banks’s The Culture novels.

As was the case with the high-rise super-cities that were imagined of the 1920s, the space-colony vision isn’t always utopian. In the 2013 film Elysium, for example, the titular space station is an exclusive haven for the ultra-rich, desperate to escape an Earth ravaged by global warming and end-stage capitalism. Perhaps this is why many people become uneasy when billionaire tech-bros like Jeff Bezos openly embrace the idea of building giant colonies in space. They seem to be confirming the dystopian side of the space colony coin.

I have very little in common with Jeff Bezos. But, like him, I must confess to be completely captivated by the idea of colonies in space. They are not only fun to imagine, but I believe that they probably do represent the best possible, long-term vision for the future of humanity. I don’t know if they will happen, but I hope they do.

Why do I harbor this hope? Lots of reasons. For one, space colonies offer our best chance of surviving as a species into the far future. Even if we somehow avoid the worst consequences of global-warming, there will always be some other looming disaster that threatens to exterminate life on Earth, from planet-killer asteroids to super-volcanoes to the next pandemic. With space colonies, there would soon be more people living in space than earth—perhaps trillions of people within a few centuries—thus making us a lot harder to wipe out.

For another, the quality of life on space colonies would probably be much, much higher for the average citizen than it is likely to ever be on Earth. This is due to the advantages I listed above, like abundant solar power and cheap resources for asteroids. And overpopulation would never be a problem—at least, not for long. Whenever a colony got too crowded, any citizens who craved more elbow-room would simply build a new space colony and move into it.

Of course, many people will never be disavowed of the idea that space colonies represent nothing more than a “Plan-B” for the ultra-rich. That is, after all the rich people trash the earth with their greed and unfettered capitalism, space colonies give them the ultimate chance for escape from the consequences of their actions.

This is, I think, a real possibility for why space colonies might eventually be built. But it’s not the only possibility, nor even the most likely. Rather, my guess is that space colonies will be built for the positive reasons that I mentioned—abundance, room, and quality of life. Indeed, one could imagine an era—in the three or four-hundred perhaps—when so many people choose to emigrate to space that Earth could become a giant Hawaii. That is, an ecological and historical preserve, with less than a billion people on the entire planet. People who are born on space colonies might endeavor to make a pilgrimage down to Earth at least once in their lives, the way many Irish-Americans eventually take a vacation in “the Old Country” of Ireland.

One thing Bezos and I vehemently disagree on (one of many things, actually) is the time-table for when space colonies will eventually be built. It won’t happen any time soon–not in Bezo’s lifetime (unless he has a store of some immortality drug stashed somewhere), nor in mine, nor in the next generation. But I think it will happen.

Which leads to the question: Will space colonies really be utopias? That depends on your definition of utopia. If a citizen of mediaeval Europe were to be magically transported to a modern, western city, they would probably perceive it as a utopia. I mean, running water? Toilets? Central heating? All the food you can eat? How much more utopian can you get? Such a person would probably dismiss any argument we might make to the contrary—that people in the 21st Century have as many problems as those in the 13th. Bullshit, they would probably say. And they’d be right. For, while modern western civilization isn’t perfect (and it seems to be getting less perfect by the day, alas), it’s still pretty freakin cool. Yes, we still have evil and stupidity and greed. And all of those human failings will find their way onto space stations.

But still, we will be making progress. It’s a worthwhile vision, and exactly the kind of dream that good sci-fi can deliver.

And should. At least some of the time.