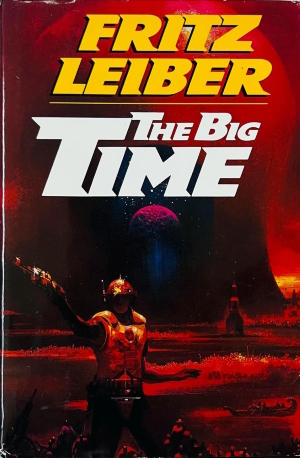

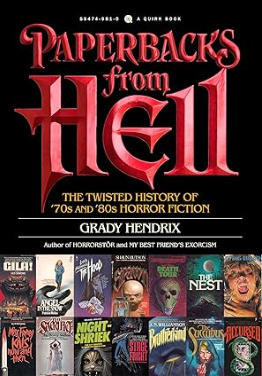

Having had exactly one book traditionally published, I am far from an expert on the world of publishing. Even so, I learned a lot more than I ever expected, and have since become fascinated by the industry as a whole. Also, I am currently working on a supernatural horror novel. So, it makes perfect sense that I would be drawn to Grady Hendrix’s excellent non-fiction book, Paperbacks from Hell, which examines (skewers?) pulp horror literature as it existed in the 1970s and 80s, both as a uber-genre and as an industry.

Let me say right up front that this is a very funny book. I found myself laughing out loud many, many times as Hendrix describes the trends and fads that overtook the genre. Take this passage where he introduces the wildly successful pop writer Robin Cook, whose 1977 book Coma is, in Hendrix’s words, the “source of the medical-thriller Nile.” As Hendrix goes on:

It all started with Robin Cook and his novels: Fever, Outbreak, Mutation, Shock, Seizure…terse nouns splashed across paperback racks. And just when you thought you had Cook pegged, he adds an adjective: Fatal Cure, Acceptable Risk, Mortal Fear, Harmful Intent. An ophthalmologist as well as an author, Cook has checked eyes and written best sellers with equal frequency. He’s best known for Coma (1977)…. Its heroine, Susan Wheeler, is one of those beautiful, brilliant medical students who’s constantly earning double takes from male colleagues or looking in the mirror and wondering if she’s a doctor or a woman—and why can’t she be both, dammit? On her first day as a trainee at Boston Memorial, she settles on “woman” and allows herself to flirt with an attractive patient on his way into a routine surgery. They make a date for coffee, but something goes wrong on the table and he goes into…a COMA!

Hendrix cleverly divides each chapter to a single, overarching trend in the pulp horror universe, with titles like HAIL, SATAN (novels of demonic possession and devil-sex), WEIRD SCIENCE (evil doctors and mad scientist-sex), INHUMANIOIDS (deformed monsters and mutant-sex), and so on. I was especially impressed by the way Hendrix explains each publishing fad as a symptom of a larger societal shift. For example, he explains how the white-flight phenomenon of the 1970s in which white middle- and upper-class families abandoned the big cities and moved to quaint, charming little towns in upstate New York or the mid-west or norther California or wherever, results in a surge of small-town horror novels like Harvest Home (wherein evil pagan matriarchs conduct human sacrifices to make the corn grow) and Effigies (wherein Satan is breeding grotesque monsters in the basement of the local church).

Another chapter entitled CREEPY KIDS, which deals with such diverse plot concepts as children who are fathered by Satan, children are who are really small adults pretending to be children, and children who, for whatever reason, just love to kill people. I particularly love this passage:

Some parents will feel helpless. “How can I possibly stop my child from murdering strangers with a hammer because she thinks they are demons from hell?” you might wail (Mama’s Little Girl). Fortunately there are some practical, commonsense steps you can take to lower the body count. Most important, try not to have sex with Satan. Fornicating with the incarnation of all evil usually produces children who are genetically predisposed to use their supernatural powers to cram their grandmothers into television sets, headfirst. “But how do I know if the man I’m dating is the devil?” I hear you ask. Here are some warning signs learned from Seed of Evil: Does he refuse to use contractions when he speaks? Does he deliver pickup lines like, “You live on the edge of darkness”? When nude, is his body the most beautiful male form you have ever seen, but possessed of a penis that’s either monstrously enormous, double-headed, has glowing yellow eyes, or all three? After intercourse, does he laugh malevolently, urinate on your mattress, and then disappear? If you spot any of these behaviors, chances are you went on a date with Satan. Or an alien.

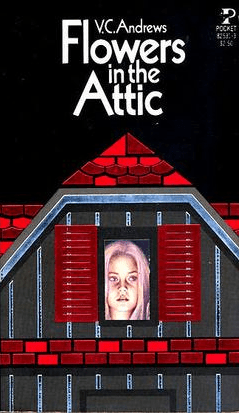

One the many things I learned from reading the book was how the entire publishing world (not just horror) was permanently changed in 1979 by an obscure tax-law case called The Thor Power Tool Co. v Commissioner. In this case, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that manufacturers could not write-down poor-selling or slow-selling inventory and thus reduce their tax liability. The case was focused on unsold parts for power-tools, but the ruling equally applied to publishing houses, who had hitherto done the same kind of write-down on their slow-selling novels. As Hendrix explains: “Suddenly, the day of the mid-list novel was over. Paperbacks were given six weeks on the racks to find an audience, then it was off to the shredder.” And so, inevitably, came the frantic scramble to find those half-dozen or so “blockbuster” books each season, behind which publishers focused their resources. (A similar “blockbuster” effect ravaged Hollywood in the 1970s, in this case due to the success of summer films like Jaws and Star Wars.) Books got less pulpy and more sparkly, with foil covers and die-cast cutouts like those made famous by the V.C. Andrews novels (which continued to be published, zombie-like, long after Andrews’s death).

Whether you’re a writer or just a pulp-paperback fan, Paperbacks from Hell is a great read. Check it out…