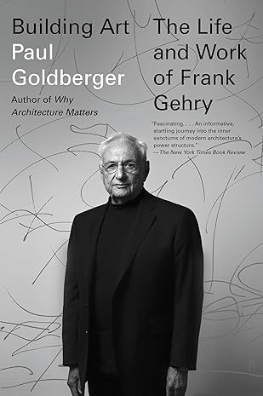

I’ve read a lot of biographies in my time. Some of my favorites have been about great monarchs (Catherine the Great by Robert Massie), presidents (Truman by David McCoullough), scientists (Oppenheimer by Kai Bird), architects (Frank Lloyd Wright by Meryl Secrest). Now, I can finally add religious leaders to my list. Or at least one religious leader, the Rebbe Menachem Mendel Schneerson.

It’s taken me this long, I think, because while I am fascinated by the study of various religions, I am not very interested in the life-story of most religious leaders. This is, in part, a consequence of the vexed historicity of such figures. Usually, they lived in the distant past, shrouded in veils of myth, with the actual, living person being lost to time. But this is not the case with Rebbe Schneerson. After all, he was not only a very recent figure, having passed away in 1994, but he spent most of his life right here in the United States—Brooklyn, in fact, that modern locus of Hasidic Judaism, and especially the Chabad-Lubavitch dynasty, which Schneerson led since 1951, succeeding his father-in-law.

As Joseph Telushkin recounts in his excellent book, Rebbe: The Life and Teachings of Menachem M. Schneerson, the Most Influential Rabbi in Modern History, Schneerson was essentially appointed to the position by general acclimation, bypassing the previous Rebbe’s son who had been the heir apparent. Community leaders and other rabbis in the movement were simply awed by Schneerson’s considerable intellect—he spoke half-a-dozen languages, had an Engineering degree, and was considered a “genius” in Talmudic study from the age of seventeen—and pressured him to take the job.

Which, thankfully, he did. I never thought I would ever read a book about an orthodox Jewish rabbi and, at the end, think to myself: “Wow, he seems like a really cool guy.” After all, I’m used to being utterly repulsed by most “leaders” in my own religious sphere, Christianity, with the exception of the current Pope and his immediate predecessor. But the more I read about Schneerson, the more impressed I was, not only by his general wisdom in matters of religion and morality, but also in his endless, practical concern for the well-being of ordinary (often poor) people, both Jews and Gentiles.

One example Telushkin provides involves Shirley Chisholm, the first black woman elected to Congress. Racist creeps in the House refused to appoint her to any high-level committees and instead stuck her on the Agriculture Committee, which, considering Chisholm represented a section of New York, seemed absurd to most observers. Yet, the snub also presented an opportunity that she, herself, never suspected. As Telushkin writes:

She soon received a phone call from the office of one of her constituents. “The Lubavitcher Rebbe would like to meet with you.” Representative Chisholm came to 770. The Rebbe said, “I know you’re very upset.” Chisholm acknowledged both being upset and feeling insulted. “What should I do?” The Rebbe said: “What a blessing God has given you. This country has so much surplus food and there are so many hungry people and you can use this gift that God’s given you to feed hungry people. Find a creative way to do it.”

And she did, creating one of the first federal food-aid programs in the history of the United States, in which surplus food was bought by the government from American farmers and distributed to poor people, thus helping the recipients, the farmers, and pretty much everyone else.

On a more personal level, Schneerson always emphasized the importance of kindness and compassion over religious stricture. In one of his drashas (sermons), he famously told the story of how his predecessor, the Alter-Rebbe, once stopped in the middle of his Sabbath observations to attend to a young woman who had just given birth and who had been left alone by her family so that they could attend synagogue. Telushkin writes:

That day, the Alter Rebbe, having somehow learned that the new mother was alone, was suddenly overwhelmed with the certainty that the woman required someone to attend to her needs immediately; it might well be a matter of life and death. And since no one else was taking care of her, he concluded that he should be the one to do so.

This story apparently shocked his followers in way that most modern, secular people like myself cannot really appreciate. The idea that a rabbi might 1.) forsake the Sabbath observations in order to 2.) do menial work on the Sabbath like chopping wood and 3.) do so for an ordinary woman was radical in the extreme.

Such was Schneerson’s boundless respect and love for ordinary people that he was always concerned about inadvertently embarrassing or insulting anyone, especially those who were most vulnerable. Decades before the so-called woke movement (a bad name for a very noble cause), Schneerson refused to use the word “handicapped” in reference to battle-maimed Israeli soldiers. Telushkin writes:

Referring to the fact that such people are designated in Israel as nechei Tzahal, “handicapped of the Israel Defense Forces,” the Rebbe addressed the men as follows: “If a person has been deprived of a limb or a faculty, this itself indicates that G-d has also given him special powers to overcome the limitations this entails, and to surpass [in other areas] the achievements of ordinary people. You are not disabled or handicapped, but special and unique as you possess potentials that the rest of us do not. I therefore suggest”—the Rebbe then interspersed with a smile—“of course it is none of my business, but Jews are famous for voicing opinions on matters that do not concern them—that you should no longer be referred to as ‘disabled veterans’ but as ‘exceptional veterans’ [metzuyanim], which more aptly describes what is unique about you.

In addition to being a genuinely good and wise person, Schneerson also seemed to have what can only be described as superpowers. He worked eighteen hours a day, six-days-a-week, for most of his life. Being busy with his primary duties during the day, he met with people seeking advice in the evenings, often as late one or two o’clock in the morning. Some of the people seeking advice including future and former Prime Ministers of Isreal such as Menachem Begin, as well as many other powerful and influential figures. But, more of than not, they were comprised of ordinary men and women in his congregation. I was especially impressed with Telushkin’s story of a young woman, Chana Scharfstein, who often came to his office seeking academic as well as personal (dating) advice:

The Rebbe clearly knew his agenda for this meeting, and the conversation quickly turned in a personal direction. At a certain point, he asked Sharfstein if she felt ready to get married. Sharfstein told him that she had begun dating—in Chasidic circles, young men and women date only for the purpose of marriage—and the Rebbe asked her about a specific young man. She recalls being taken aback and thinking to herself, That’s interesting that he should ask about somebody that I had met. Sharfstein told the Rebbe that she had met the young man he mentioned, that he was clearly a fine person, but not for her. The Rebbe said all right, and then mentioned another name, and again it was someone to whom Sharfstein had been introduced. Here, too, the young man was very nice but not for her. Then the Rebbe mentioned a third name, and a fourth, “and I became really uncomfortable then. How did the Rebbe choose all the names of young men (bachurim) that I had met? I was just absolutely overwhelmed that he should mention people that I had actually met.” Only later did she learn that prior to going out with a girl, each bachur in Chabad would write to the Rebbe to inquire if the girl seemed suitable for him, and so the Rebbe, who obviously had responded in each case that Chana Zuber was suitable, had a very precise idea of all the people with whom she had gone out. But even taking all this into account, Sharfstein still remained staggered at the Rebbe’s recall. After all, he “was [already] a world leader at this time, and to keep track of each person and who had been dating whom, it’s really mind-boggling.”

As this story relates, Schneerson’s remarkable memory and formidable intelligence were often sources of awe among those in congregation. Another example involves a young student, Irving Block, who came to discuss philosophy with the Rebbe:

At the time, Block, who was studying for an MA in philosophy, was immersed in the study of the great Greek thinkers, Plato in particular. And that’s the direction in which the Rebbe led the discussion. Only Block didn’t realize at first to whom the Rebbe was referring, because it was a man named Platon about whom the Rebbe started talking. It finally struck him that Platon is how the name of the Greek philosopher is written in Greek, though in English his name is always pronounced as Plato. It’s not that the n is silent in English; it isn’t written at all. This was Block’s first surprise of the day. The man seated in front of him, dressed in the garb of a Rebbe, obviously knew about Plato, or Platon, from the original Greek and pronounced his name as it was supposed to be pronounced.

Block was not only amazed by the Rebbe’s deep understanding of the “Platon’s” philosophy but by his utter rejection of it. (Plato believed that the nuclear family was an evil institution and should be abolished, an idea that was in direct contradiction to all humanist values, including those of Judaism.)

In recounting such stories as these, Telushkin’s book is really more of an appreciation or tribute than an in-depth biography. And yet he manages to relate the primary facts of Schneerson’s remarkable life with grace. Born in Imperial Russia, Schneerson moved with his family to the US in the spring of 1941. Thereafter, he served as Rebbe for over 50 years, finally passing away in a time when the world was much changed.

One might say that he was born in the time of Tsars and passed away in the time of the internet. And, in all that time, one thing remained constant: his steadfast commitment to the practical well-being of all the people, rich and poor, high and low, in his community and around the world. Truly a person worth reading about. Check it out…