Fourteen years have passed since Skyfall, the twenty-third installment in the James Bond franchise, was released. The Daniel Craig era is now over, and the entire Bond series has just been dumped onto Netflix until a new actor is anointed and the series can undergo yet another reboot.

Of course, I have no idea who Eon Productions will pick as the new Bond, but I do know that he will have very large shoes to fill. Craig, who was initially dismissed as a blond pretty-boy, came to inhabit the role in its best incarnation since Sean Connery’s. With his baleful stare and ruthlessly sculpted physique—a body that, by its very existence, suggested military fanaticism—Craig interpreted Bond as a high-tech samurai, patrolling the alleyways, caves, and tunnels of the criminal underworld. This was a new, modern Bond. He still drank, but didn’t smoke. And where previous Bonds were sexually rapacious, Craig’s version seemed almost indifferent to the beautiful, amoral women surrounding him. Indeed, in the Craig era, it was the women who initiated all the lovemaking. For Bond himself, sex almost seemed like an afterthought, a distraction from his real objective: revenge.

I have written before about the revenge-fantasy as a seldom discussed—but hugely popular—Hollywood genre. And it seems very probable to me that the current explosion in the genre’s popularity, from the John Wick movies to Taken to Sisu and on and on, originally stems from Daniel Craig’s Bond. The best movies of the Craig era are, implicitly, revenge fantasies of a sort. From the very first film, Casino Royale, Craig’s austere expression and muted affect both imply some horrific past trauma, an experience of loss which transformed him into a fearless, disciplined operative. A killer looking for vengeance.

Of course, the central mystery of the Craig films, and a huge part of their appeal, lies in what, exactly, Bond is seeking vengeance for. And on whom? None of the films explores this mystery as deeply and effectively as Skyfall.

In one early scene, Bond, still traumatized from having almost been killed on his last mission, is forced to undergo a psychological evaluation. The bearded shrink asks him to play a word-association game, to which Bond reluctantly submits. When the shrink gives him the word “Skyfall”—the first mention of the term in the film—Bond’s expression freezes into a rictus of rage, pain, and contempt. He angrily ends the interview and storms out.

Not only is this scene a brilliant way to introduce the Skyfall term into the discourse of the film (“What could it be?” the viewer wonders), it also acts as a kind of clue to that deeper mystery to which I previously alluded. That is, the mystery of why Bond is so damned angry. We sense, immediately, that it has something to do with Skyfall (whatever that is), and that it involved some horrific trauma that Bond suffered in his past. Thus, it becomes the biggest clue in the psychological whodunnit of the movie, the mystery that we, as viewers, want to solve.

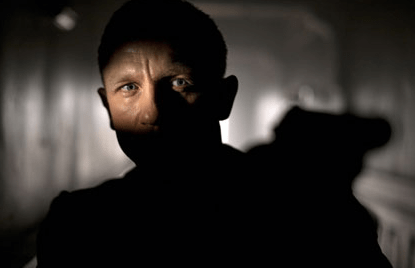

When I re-watched that scene recently, it occurred to me that if someone were to play the word-association game with me and mention “Skyfall,” my response would be “blue.” For if one had to pick a single word—both a color, and an emotion—that best sums up the film for me, it would be that: blue. It is the dominant palette of the movie, as well as its defining mood. In the film’s opening frames, Bond emerges from the shadows until half of his face is illuminated by a slender shaft of light, the viewer’s attention is drawn immediately to Craig’s cold, cobalt-blue eyes. Similarly, the last act of the film takes place in the wintery, blue-grey wilderness of Scotland, which surrounds Bond’s ancestral home—the vaunted Skyfall—a land which seems bleached of color, if not life itself.

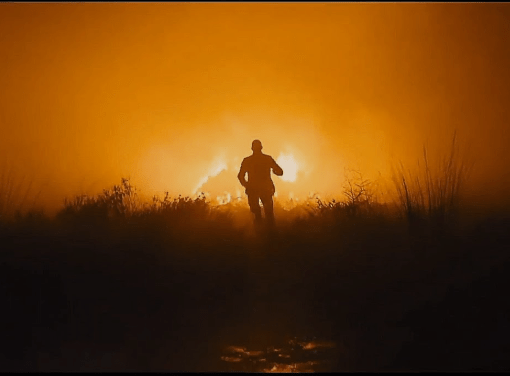

Everything in between these opening and closing movements is equally cold and blue. The only real counterpoint is the yellow blaze of fire. Specifically, fire becomes an equal, opposite visual symbol in the film. In one scene, Bond stands at the bow of a rickshaw as he is rowed into the dark domain of a Macau casino, itself surrounded by hundreds of tiny, floating candles. Later, a different kind of fire—the flames of the burning Skyfall house—illuminate the cold, night-shrouded landscape in which Bond’s final confrontation with Silva, the villain, takes place. Such moments of stark, warm firelight only emphasize—accentuate—all the blue coldness that dominates the movie physical and psychological fabric. In the battle between fire and ice, the movie warns, ice eventually wins.

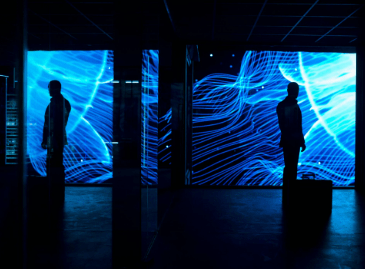

The most famous and talked about moment of blue-ness in the film comes in the middle of the second act, during a scene that some action-film-loving bros find maddingly slow. Bond stalks his quarry—an assassin named Patrice—into a Shanghai office tower at night. He follows Patrice to a high-level, empty floor that is completely shrouded in darkness, except for the unearthly, swirling blue light pouring in from a digital ad sign. It’s a completely silent scene that evokes more cinematic antecedents than I can count. There’s a good deal of Blade Runner in it, as well as Point Blank, Klute, The Mechanic, and many others. Beyond all that, even, the glass walls inside the builder make the scene into a classic Hall of Mirrors trope, which has been used repeatedly throughout the history of cinema to represent a journey into the subconscious—the battle against the self. And it works perfectly here, for what is Patrice if not a mirror image of Bond? They are both cold, disciplined killers, separated from any meaningful, human connection.

As the scene continues, Bond takes no action as Patrice prepares to assassinate a man in the building across the street. It’s only after Patrice does the deed that Bond takes action, jumping him and eventually knocking him out an open window. Fortunately, Bond finds a gambling chip that Patrice left behind, which allows Bond to impersonate him at a Macau casino. Thus, the twinning is complete.

The film’s arch-villain, Silva (brilliantly played by Javier Bardem), is also a twin. Another linked opposite. Silva, another 007 agent, was betrayed by MI6 in the same way Bond felt himself to be when he was shot by friendly fire in the film’s opening. And, like Bond, Silva has devoted his life to a single-minded purpose: revenge. The viewer doesn’t know who, exactly, Silva wants to inflict his revenge on, but we suspect it’s M, to whom Silva refers as “Mommy.” Talk about psychological baggage!

In this way, M (again, brilliantly played by Shakespearean actor Judy Dench), the steely-eyed matriarch of MI6, becomes the symbolic heart of the film, and the key to its structure. She represents a mother figure to both men, Bond and Silva. But whereas Silva wants to kill her, Bond decides to protect her.

That’s one reason why the setting for the film’s climax—Bond’s home, Skyfall—works so well. Bond has “come home” both literally and psychologically, protecting the woman who represents a substitute for the mother (and, in some ways, the father, too) that he lost as a child. In the final shootout, Silva “comes home,” too, and inevitably finds himself alone with Bond and M in church. It’s a great scene that feels like an Oedipal love-triangle, or perhaps a re-staging of the Cain and Abel story, or some other classic, archetypal conflict. It’s a great ending to a great film.

In fact, if Skyfall is not the very best James Bond movie of them all, it’s way, way up there. Directed by auteur, literary film director Sam Mendes (whose first film, American Beauty, won him an Oscar), Skyfall is also, in the ways that I have discussed above, the deepest Bond movie. The heaviest. With all its angst, psychologic trauma, and absurdist violence—not to mention all the arctic blues—it almost feels like an existentialist art-film. If Kierkegaard were to make a Hollywood action movie, this would be it.

No, really. I’m serious. The real difference between Bond and Silva (and Patrice) is that he struggles. He wrestles with the central theme of the movie—the question of how can a warrior be sure that the people he serves (M, in this case, and MI6 generally) are any better than the enemies he has been tasked to destroy?

Bond feels betrayed by M, and by the entire system she represents. Over the course of the narrative, though, he slowly regains his faith. When M eventually confesses what she did to Silva (giving him up to the Chinese in exchange for six other agents), he accepts her justifications as moral (if incredibly troubling). He stops seeking vengeance on the world, and he decides to protect M, even at the cost of his own life.

On the other end of the spectrum, Silva is completely selfish in his pursuit of revenge. He has no self-awareness of his own culpability in the ordeal he suffered. (M sold him out, in part, because he was enriching himself using his talents.) Nor does he make any attempt to understand why M did what she did. In this way, he becomes a brilliant, terrifying villain who is, nonetheless, a completely hollow man. He has no real personality, other than a kind of sneering arrogance. There is nothing left of him except his hatred.

Good versus evil. Heroism vs selfishness. It’s all in there. That’s why Skyfall is a perfect film.